Cool air flows inside my denim trucker and through my gauzy shirt as I step into the North Yarmouth Academy ice arena. The ice is gone, revealing a polished cement floor perfect for trikes and go carts, which children are piloting like bumper cars at a carnival. One of them is my ten-year-old son Calvin, who I am surprised to see wheeling his way around the vast arena on a durable, red, chopper-style tricycle. The speed and finesse he exhibits astonishes me, though not as much as his apparent ability to steer the thing (for the most part.) It’s not an adaptive trike, but his physical therapist has outfitted it with Velcro foot straps and a safety belt so he can cruise with little risk of injury. I approach Calvin, who is with his one-on-one Mary. I call his name in a way he'll recognize, and by the time I swoop in for a hug and kiss he’s sporting a big, toothy smile. It has only been in the last year or two—perhaps three—that I’ve felt confident that Calvin knows who I am, and even then I’m sure he recognizes me by my voice more so than by my form or face.

Today, a community of disabled children and young adults have gathered for part two of the Special Olympics, this one an indoor version with various stations for the participants to enjoy. There’s a basketball hoop short enough for someone seated in a wheelchair to make a dunk, a bowling station complete with dense Nerf balls and pins, and a sensory table equipped with cause and effect toys that light up, vibrate, buzz and bark when the user touches them in a particular way.

A few minutes after my arrival, a flood of neatly dressed children stream through the door and into the arena. As far as I can tell they look to be in their early teens. Handsome boys wear shirts with ties and slacks. Some are wearing sweaters. Long-haired girls are dressed in skirts and leggings, skinny pants and boots, blouses and cardigans. All are quiet, serious and watchful.

The Academy students, of which there seem to be between fifty to a hundred, are here as volunteers to assist in the Special Olympic activities. They first form a large ring facing outward, around which the disabled youths parade alongside their teachers, aides and therapists. The prep-schoolers applaud my son and his classmates as they pass by, the din of clapping and cheers ricocheting off of the hard angles of the space and the wheelchairs, trikes and braces. I watch all of the children and marvel at the contrast between smiles and grimaces, between lithe and long arms versus crooked or clawed, between calm, thoughtful, intelligent minds versus seizure-racked and broken brains. I wonder what these "typical" kids make of my son and his classmates, of the contorted bodies and faces of the young adults being wheeled by, of the disabled flock that they have come to honor at this event.

From the opposite side of the glass I see a man, perhaps my age, weaving his way through the crowd of kids. He's tall and slender, dressed in a dark suit and I imagine him to be one of the teachers, perhaps the principle. He has a kind face and demeanor and when he glances my way we both smile. I want to thank him and his students for their time and concern, but when I head out onto the cement rink to find him, he is gone.

Off to the side I see Calvin having a try at bowling. With help, he pushes the Nerf ball down a sloped track and knocks down all but one pin. He tries again and knocks down all but two. A third attempt spares but one, and when the surrounding group cheers he doesn't smile, which makes me worry. The pins make me think of his seizures, how no matter what we hurl at them, a few remain steadfast.

I gather Calvin into my arms and kiss him all over, making him smile, which relieves me some. I can feel the Academy students watch us—perhaps as a spectacle, though hopefully with plain curiosity for their expanding universe. I wonder what they think about this mother's show of deep affection for her awkward, legally blind, wordless, drugged-up, messed-up kid. I wonder if they think of themselves, wonder if they think of their own mothers, wonder which ones will take this experience and run with it, and which ones will simply run away.

Today, a community of disabled children and young adults have gathered for part two of the Special Olympics, this one an indoor version with various stations for the participants to enjoy. There’s a basketball hoop short enough for someone seated in a wheelchair to make a dunk, a bowling station complete with dense Nerf balls and pins, and a sensory table equipped with cause and effect toys that light up, vibrate, buzz and bark when the user touches them in a particular way.

A few minutes after my arrival, a flood of neatly dressed children stream through the door and into the arena. As far as I can tell they look to be in their early teens. Handsome boys wear shirts with ties and slacks. Some are wearing sweaters. Long-haired girls are dressed in skirts and leggings, skinny pants and boots, blouses and cardigans. All are quiet, serious and watchful.

The Academy students, of which there seem to be between fifty to a hundred, are here as volunteers to assist in the Special Olympic activities. They first form a large ring facing outward, around which the disabled youths parade alongside their teachers, aides and therapists. The prep-schoolers applaud my son and his classmates as they pass by, the din of clapping and cheers ricocheting off of the hard angles of the space and the wheelchairs, trikes and braces. I watch all of the children and marvel at the contrast between smiles and grimaces, between lithe and long arms versus crooked or clawed, between calm, thoughtful, intelligent minds versus seizure-racked and broken brains. I wonder what these "typical" kids make of my son and his classmates, of the contorted bodies and faces of the young adults being wheeled by, of the disabled flock that they have come to honor at this event.

From the opposite side of the glass I see a man, perhaps my age, weaving his way through the crowd of kids. He's tall and slender, dressed in a dark suit and I imagine him to be one of the teachers, perhaps the principle. He has a kind face and demeanor and when he glances my way we both smile. I want to thank him and his students for their time and concern, but when I head out onto the cement rink to find him, he is gone.

Off to the side I see Calvin having a try at bowling. With help, he pushes the Nerf ball down a sloped track and knocks down all but one pin. He tries again and knocks down all but two. A third attempt spares but one, and when the surrounding group cheers he doesn't smile, which makes me worry. The pins make me think of his seizures, how no matter what we hurl at them, a few remain steadfast.

I gather Calvin into my arms and kiss him all over, making him smile, which relieves me some. I can feel the Academy students watch us—perhaps as a spectacle, though hopefully with plain curiosity for their expanding universe. I wonder what they think about this mother's show of deep affection for her awkward, legally blind, wordless, drugged-up, messed-up kid. I wonder if they think of themselves, wonder if they think of their own mothers, wonder which ones will take this experience and run with it, and which ones will simply run away.

|

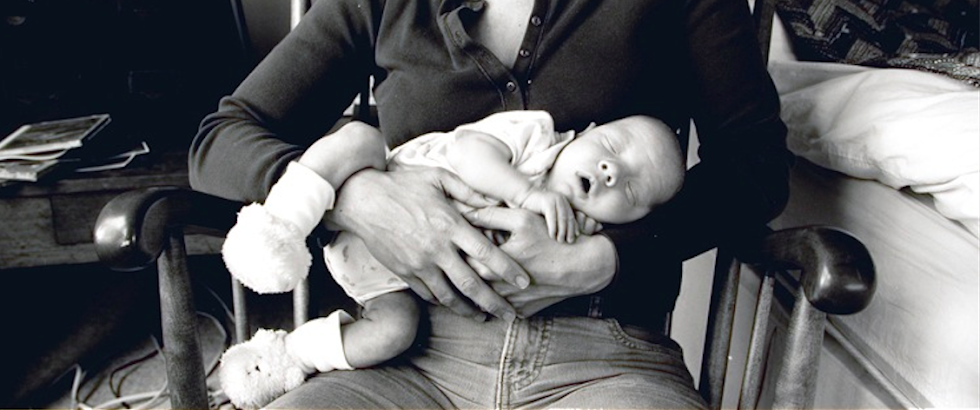

| Calvin on his trike at last year's Special Olympics at the North Yarmouth Academy Arena |

Having traveled through childhood and adolescence with an awkward, legally blind, hearing aid wearing, retarded sibling, I was always sensitive to what "normal" kids thought about our weirdness. It was especially distressing if a compassionate helper from one venue became a merciless critic in another. But then I realized that I was both too. There are times that I must run away from my sister to avoid cruelty. And even times (fewer now that I am a grown up) when I am simply cruel. So I conclude that we all have the very same struggle between loving kindness and distancing scorn. If some of the NYA kids mock the event afterwards, that doesn't mean that they didn't have a profoundly moving experience at the same time. And for others, it all may have seemed perfectly normal. A little schadenfreude perhaps, or "there but for the grace," but not much more than when they meet someone with more zits or less money. The fabulous thing about the Special Olympics is that it is a public celebration of difference. The joy it brings to everyone is palpable. Thank you, Eunice Kennedy Shriver. And thanks, Christy, for reminding me of some great times with my sister, Christianne Michelle. She has a closet full of Special Olympic medals and ribbons. Like you, she was a swimmer when she was younger.

ReplyDelete