The sky opened up at one a.m. I rose from a deep dream to shut windows in the house so the rain wouldn't come in. As I was lowering one sash, I heard the quick slap-slap of a runner's gait on wet pavement. Peering out, I saw a guy run past under the streetlight. I recognized him. A youngish man compared to me, I'd met him in town years back. We had exchanged pleasantries. Later, I had greeted him several times as he ran past me on the street and in the trails around the field, his waif-like frame, bony limbs and gaunt face as distinctive as his long wavy hair and shy smile. Had he been caught in the deluge? Or had he—perhaps anorexia's captive—been compelled to run despite the storm's arrival? Or, had running in the middle of the night been his liberation, his savior, like writing and gardening have saved me from the grief-grip-loss that my son embodies?

When I put Calvin on the bus yesterday we were no doubt floating within a cloud, its sprays of mist collecting on our heads, dripping from trees, droplets adorning webs and beading up on leaves. If not for a good breeze, the humidity would've proven oppressive. Later, on my way back from a walk with Nellie, I stopped to talk with a neighbor. A nicely-dressed woman drove up curbside and exclaimed that she was looking for a notorious local man so she could run him down. The man she hunted had been seen recently knocking and entering open homes in the area, taking cash and jewelry, ostensibly to support his heroin addiction. Police confirmed that I'd seen the stranger earlier that morning knocking on the door of a home down the street. Though I didn't see him enter, somehow I'd thought his incessant knocking odd, so I memorized his description: white guy, medium build, brown hair, early forties, khaki shorts, dark hikers or sneakers, long-sleeved tee.

I winced when the driver, a colleague of Michael's who I don't really know, said she wanted to run this guy over. She claimed he was violent. I gently (hopefully) challenged her notion, but she could provide no supporting evidence. I tried to imagine what I would do if I were in his condition. I remembered a piece I heard about a former addict who described what addiction was like. I told the woman I thought it sad that the guy was in such a state that he needed to steal from others. She lamented she'd been dealing with him for years. I wondered what I'd do if I came across him, wondered if I'd give him a buck or two.

Troubled, I removed myself from the conversation, crossing the street to visit with Woody who was sitting on his porch. He was familiar with the man police were pursuing. The man's family, Woody said, had always had some sort of trouble as long as he could remember. I expressed my regret that anyone get hooked on opioids, knowing full-well—contrary to popular myth—that the average addict begins with opioids prescribed for pain by unwitting and/or cavalier physicians. Woody said the guy should get some help. I countered by admitting that I'd never been addicted to a substance, but that I imagine heroin must be nearly impossible to kick, perhaps even making it difficult to seek—or even want—help.

What flashed through my mind next was a glimpse of how others might view me and Calvin; I wondered what kind of judgment family, friends and strangers pass on us—what did she do wrong while pregnant? why is she so strict with her son? why so lenient? why is she so demanding and impatient? why is he so wild? why is she so skeptical, so harsh? why does she let him get away with this, yet make him do that?

I pondered compassion and what I see as today's empathy gap, which is widening in an increasingly polarized nation with a self-obsessed, callous man at the helm.

At the close of the day, while putting on Calvin's nighttime diaper and pad, giving him his cannabis oils and Keppra, and brushing his teeth, I listened to a piece on National Public Radio. Journalists spoke with the Idaho Director of Agriculture and to a pig farmer who described the hardship in the face of the warring trade tariffs that The Donald put in place. Hearing their distressing stories, I got teary.

"No one deserves to suffer like that," I said to Michael, "even if they voted for him."

Michael, though he agrees with me that support for The Donald is short-sighted at best, expressed his dubiousness that any of us is deserving of anything—beyond human rights such as healthcare and education—whether it be good or bad. I get it.

As the news segment closed, a wave of sorrow washed over me, leaving me wishing relief for the hard-working farmers, many who risk losing their businesses because the tariffs stand to strangle the decades-long, worldwide trading relationships they've developed. I went to sleep thinking of them.

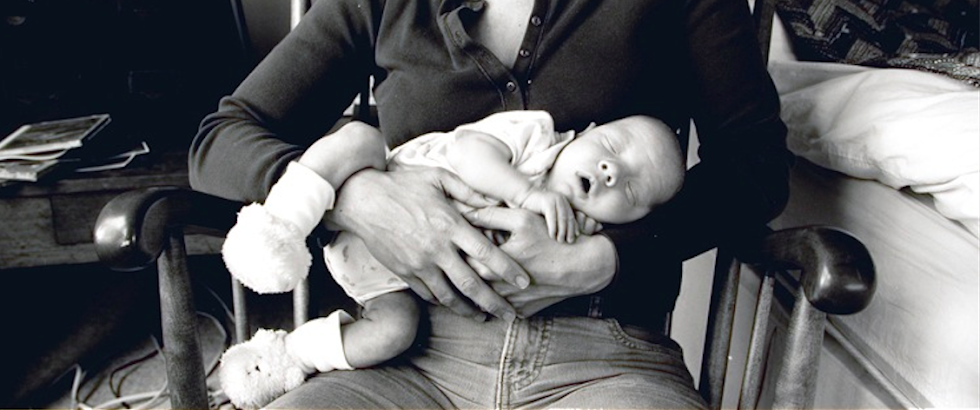

Hours later, in the shiny black after midnight, I watched the jogger sail down the street into darkness, the driving rain matting his hair, his spine and ribs exposed beneath a soaking shirt. I wondered if he was cold. I thought of the petty thief rummaging desperately through strangers' homes just to get enough dough for his next fix. I wondered if he is lonely. I thought of the farmers, heads in hands, families to feed, crops and livestock and legacies in jeopardy, and I wondered how they'll cope. I thought of my sweet, innocent, unknowing Calvin sleeping upstairs, seventeen days since his last grand mal seizure. It's no matter, but empathy gave me some trouble falling back to sleep.

No comments:

Post a Comment