calvin's story

12.19.2023

hurricane force

11.16.2023

on running

A little less than two years ago I began running in earnest for the first time in my life. My dear friend, Olympic gold-medalist and world-class marathoner, Joanie Benoit Samuelson, knowing that I had once been a division I swimmer, had been asking me for years, "When are you going to get back into the pool?" and, "You know, swimmers make good runners."

I had long lost interest in swimming for fitness, in doing lap after boring lap despite how good my body felt moving swiftly through the water. But I was desperate to feel like my former athletic self. More so, I pined for an escape, a respite—even if only fleetingly—from the responsibilities of taking care of my autistic, disabled, chronically ill child, Calvin. I yearned for something to occupy my mind besides the worry, anxiety, frustration and disappointment that loom too large caring for someone like him. I needed something that was wholly mine.

For the first fifteen months of the pandemic—before Covid vaccines were developed—we didn't send Calvin to school, didn't take our usual outings to the grocery store, and had given up our in-home nursing help. To pass the time, Calvin and I went for daily drives on the nearby backroads taking in the beautiful scenery and listening to music. On our drives I often imagined pulling over, getting out of the car and running into the vast meadows just to lose myself. It was during our drives that I spotted an ambitious and wicked-quick runner who glided for miles and miles even in the harshest weather. I wondered what compelled him to run so far, wondered if he, like me, felt driven to run from some sadness, burden or worry, toward some kind of reward, or perhaps a little of both.

A year later, Joanie gave me a pair of fancy running shoes in exchange for an ice cream cake I had made for her husband's birthday. That was the moment I knew I had to commit to training for her world-renowned Beach to Beacon 10k, which she founded in 1998 and in which she had urged me to participate. It would be my first road race ever, and one that would get me hooked on the sport and on competing again.

Since that first race in August of last year, I've competed in four 10ks, three

5ks, one ten-miler, and a half

marathon, which was in early October. I've enjoyed some small successes. Mostly, though, running has done for me what I hoped it would. I feel like my old

self again in many ways—more light and lithe and spry. I'm healthier and happier. My capacity to endure my son's troubles has, perhaps, expanded. I think—hope—I'm a better person, friend, wife, mom. I've befriended some sweet and amazing people whose generosity, expert advice and encouragement has

been essential to my accomplishments.

Getting out

on the trails and roads, especially at my beloved Pennellville with its big sky, open fields, and expansive views across the water has been cathartic. I love to

feel the sun and rain and wind—and sometimes snowflakes—on my face.

The one downside, however, is that I've been writing a lot less. Notably, though, when running, I almost never think of Calvin (and therefore I don't feel at all stressed or anxious.) I hear only the sound of my breathing and my feet striking the ground, the swish of my jacket, the song and chirp of birds and crickets, the babbling of brooks. I smell the sweetness of fresh-cut grass, clover, rose rugosa, smoke from a wood stove. I smile and wave at passing runners, bicyclists, truckers. I drink in whatever Maine has to offer on any given day throughout the year. I lose myself. In short, I finally have a time and place where I feel free.

Last week I signed up for the New York City Half Marathon in March with the hope of running with 24,000 other athletes over the Brooklyn Bridge, up Seventh Avenue and into Central Park (thanks to John Blood for that recommendation). I qualified for the event, but I missed the cutoff date for the guaranteed timed entry, so I'm hoping to be chosen in the random lottery which is at the end of this month. Cross your fingers, knock on wood.

I'll be forever grateful to the many lovely people who have brought me to this sublime place called running: my father, our family's original athlete who ran a 4:28 mile at the Naval Academy in 1948; my husband, Michael, who has been running four or five fast 5ks every week for nearly a decade; Joanie Benoit Samuelson, for urging me on for so many years; Rob Ashby, marathoner extraordinaire, who unwittingly inspired me to go the distance, and so many others since who have inspired, supported and encouraged me to keep on trucking. Thank you.

11.03.2023

recent dealings

and then, this poem reappears:

10.16.2023

dear friend

now i will be strong for you. i can. you will stay in my thoughts and you will shine. i know. focus on the little things. the smell of your coffee, the feeling of the sun on your face. the wind in your hair. the quiet of a back road. the taste of clover and salt in the air. the warmth of a loved one's hand. the feeling and sound of the ground under your feet ... tarmac ... carpet ... tile ... wood ... rubber ... linoleum ... sand .... grass. the happy din of knives and forks on a plate. the rich taste of dark chocolate. the sound of bees and birds and brooks—even the memory of them. the color of the sky at dawn. at noon. at dusk. in the middle of the night. the patter of rain on a metal roof. the beauty of wilting flowers. the happy creases in the corners of smiling eyes. the long embrace of a friend. the light caress of shower water as it trickles down your back. the smoothness of soap in your hand. the buzz of a crowd. linger on these little things and let them move you. let them make you weep. they can be a joy in and of themselves. let the other big stuff take a backseat, if only for a moment. know you will remain in my thoughts. know i will listen and be there for you. as you have been for me. because, despite my own burdens (everyone has them) i have an infinite reserve of strength for you.

10.06.2023

sixty

Despite

the fact that nineteen and a half years of stress, sleep deprivation, and frustration from raising Calvin has likely shaved a few

years off of my life, in my mind, spirit, and most parts of my body I

still feel thirty-six. Regardless, I woke up this morning entering my sixtieth year

of life, and though the wee hours of my birthday began with a restless Calvin

suffering from some sort of pain, from my perspective—one in which I try to practice gratitude, even for the mundane—life still looks

decently rosy.

That fact is a testament that we humans are

resilient as shit, most of us able to handle the nasty curveballs hurled

our way at different times in our life. I don't believe in the

notion that everything happens for a reason and/or that God doesn't give us more than we can handle (I don't

believe in that kind of god, anyway) because I have seen pain and anguish push people I love over the brink. However, I do believe there is a

lot of good most of us can glean from bad things that happen to us. We can find

the generous pluses, for instance, amid the scores of miserable minuses

that a disabled child brings in the form of loss, guilt, despair, anger,

resentment, heartache, suffering, pain, sorrow, hopelessness, envy,

frustration, doubt. My sweet Calvin has brought me joy, love, patience,

empathy and the rare chance to witness a life that, if it weren't for

his physical pain, is as close to nirvana as any human might hope to

get.

I have learned from Calvin how trivial material desires can

be, how petty some quarrels are, and I am getting better at

understanding how little it matters that he can't run on a cross-country team, can't speak two languages—much less one—can't excel in math

and science, can't work a computer, can't even trick-or-treat. Daily, I

hear stories of children—and their parents—who deal with seizures or

hunger or pain or disease far more heinous than Calvin's circumstance. And I feel so grateful that Calvin is simply warm and dry and safe and mostly happy

and living with a forever-evolving sixty-year-old mom who feels twenty-plus

years younger, and still feels up to taking on the world.

9.22.2023

rough patch

Sadly, the next day Calvin suffered back-to-back grand mals amid a low-grade fever. Four days later he tested positive for Covid despite not having any significant respiratory symptoms. It might sound strange to you, but I was actually relieved to know that he had Covid, which meant at least there was a knowable trigger for his grand mals as opposed to them just happening out of the blue. It will be interesting to see if he can go another months-long stint after he recovers. If history is any indicator, he may not.

And so, this past Monday was Calvin's tenth day at home resting, and during that time my patience thinned more than I'd like to admit. Calvin remains restless as ever, likely because of the drugs he has used in the past and/or the ones he is taking now. He still bites surfaces incessantly, and has begun to lean over and beaver away at the molding on the walls to either side of where his jumper hangs, he's that tall. He puts his fingers in his mouth and drools as much as ever, and puts his hands on my face constantly, so it is a miracle that I haven't gotten Covid from him. He has had terrible trouble falling asleep, and instead bangs on the wall or kicks the inside panel of his safety bed sometimes for hours despite being laid back down often. It drives me and Michael up the wall as it is impossible to ignore. We aren't sure why Calvin is tossing and turning as much as he has been since the Covid. It might be because of the Covid, but we can't be certain.

It's blogs like these that cause me to consider scrapping it all together. I've become weary of writing the same damn thing over and over for almost thirteen years. Nothing seems to really change. I imagine a lot of you are tired of reading about the tedium, too. I'm not sure I'm learning anything new by exploring the same topics ad nauseam. Moreover, I want to feel less of the things that make me worry and mad and anxious. And it's hard not to believe that putting this stuff down in words isn't doubling the insult to me and my readers.

Sigh.

On a couple of non-Calvin-centric notes, I've continued running and have been training for my first half marathon on October 1st. I love the way running makes me feel free, alive, and unencumbered. I'm also assistant coaching a parks and rec kindergarten through sixth grade co-ed cross-country team like I did in the spring, and it is so much damn fun.

Calvin is back at school and no longer has to wear a mask. He's begun eating better again, and last night was slightly more restful than of recent. Here's to hoping this recent rough patch is soon over. Cross your fingers and knock on wood.

9.11.2023

get ready to cry

Long ago, my brother Scott forwarded an email to me. On first glance, it

appeared to have been one of those chain emails that I loathe receiving,

the ones that, at the end, tell you that you must forward it to others

and something good will happen to you. But it was not one of those.

Rather, it was a list of incidents relating people's humanity, empathy,

gratitude and grace, and what made it even nicer for me was its absence

of any mention of God; it was simply an account of the amazing creatures

we can be if we are open, loving and mindful of others.

Thank you, Scott, for knowing that this was something I'd appreciate,

even though I'm often cynical and despondent, and for sending it on.

Here it is for the rest of you. Enjoy:

Today,

I interviewed my grandmother for part of a research paper I'm working

on for my Psychology class. When I asked her to define success in her

own words, she said, "Success is when you look back at your life and the

memories make you smile."

Today,

I asked my mentor - a very successful business man in his 70s- what his

top 3 tips are for success. He smiled and said, "Read something no one

else is reading, think something no one else is thinking, and do

something no one else is doing."

Today,

after a 72 hour shift at the fire station, a woman ran up to me at the

grocery store and gave me a hug. When I tensed up, she realized I didn't

recognize her. She let go with tears of joy in her eyes and the most

sincere smile and said, "On 9-11-2001, you carried me out of the World

Trade Center."

Today,

after I watched my dog get run over by a car, I sat on the side of the

road holding him and crying. And just before he died, he licked the

tears off my face.

Today

at 7AM, I woke up feeling ill, but decided I needed the money, so I

went into work. At 3PM I got laid off. On my drive home I got a flat

tire. When I went into the trunk for the spare, it was flat too. A man

in a BMW pulled over, gave me a ride, we chatted, and then he offered me

a job. I start tomorrow.

Today,

as my father, three brothers, and two sisters stood around my mother's

hospital bed, my mother uttered her last coherent words before she died.

She simply said, "I feel so loved right now. We should have gotten

together like this more often."

Today,

I kissed my dad on the forehead as he passed away in a small hospital

bed. About 5 seconds after he passed, I realized it was the first time I

had given him a kiss since I was a little boy.

Today,

in the cutest voice, my 8-year-old daughter asked me to start

recycling. I chuckled and asked, "Why?" She replied, "So you can help me

save the planet." I chuckled again and asked, "And why do you want to

save the planet?" " Because that's where I keep all my stuff," she

said.

Today, when I witnessed a 27-year-old breast cancer patient laughing hysterically at her

2-year-old daughter's antics, I suddenly realized that I need to stop complaining about my life and start celebrating it again.

Today,

a boy in a wheelchair saw me desperately struggling on crutches with my

broken leg and offered to carry my backpack and books for me. He helped

me all the way across campus to my class and as he was leaving he said,

"I hope you feel better soon."

Today,

I was traveling in Kenya and I met a refugee from Zimbabwe. He said he

hadn't eaten anything in over 3 days and looked extremely skinny and

unhealthy. Then my friend offered him the rest of the sandwich he was

eating. The first thing the man said was, "We can share it."

8.31.2023

what matters

While grasping Calvin's wrist, we limped along the narrow road toward the water. Every few seconds I wiped drool from his chin with the corner of the bandana tied around his neck. He grimaced as the wind whipped his hair and the sun beat his face. A couple hundred yards further, when we reached the tip of Simpson's Point, I plopped him down at the top of the decrepit cement boat launch. It was a stunning day, and the mild waters of high tide had attracted the usual crowd of sunbathers, swimmers and waders.

We sat for a spell and visited with a few friends before a Parks and Recreation employee approached and instructed me to move my car because the back bumper extended inches beyond a no-parking sign. I hadn't noticed my error when parking, nor had I noticed it when I had wrangled Calvin out of the car, making sure neither of us would careen into the ditch at the shoulder. And though I was peeved that we had to leave our perch prematurely, I was grateful that we'd had a few minutes to soak up the sun before our day's "adventure" was cut short. On the way back to the car, the employee again approached and said he'd been wrong, that my car wasn't over the mark. By then, however, having made Calvin walk all way the back to the car, I decided it was best just to leave than to make him do it all again.

All summer, and especially on weekends, I've been lamenting my imprisonment with Calvin (Michael usually works several hours on Saturdays and Sundays, too, and Mary usually can't help on weekends.) Though Calvin has not had a seizure in over four months, lately, he seems restless as ever, and less interested in spending time in his beloved jumper, which means more of our time is spent walking in endless loops around the house and yard, and driving loops around the back roads in the car.

I had been mourning my loss again—the loss of not having had a healthy child. If things hadn't gone so wrong nineteen years ago, on a day like Sunday Calvin likely would have been off on his own, hanging out with friends, traveling the world, going for bike rides and runs, to the beach, to the park, on a boat ride, paddling, water skiing, fishing, skateboarding, hiking. Who knows?! And I'd be enjoying the day to myself, or with Michael even, perhaps in the garden or at the shore with a book in my lap, or simply walking a long stretch of beach without a little ball and chain weighing me down.

Later on, I took Calvin to the grocery store. We go there virtually every day. He likes to push the cart—it seems to make it easier for him to walk—while I steer it from the front. Even before entering the store, he gets a big grin on his face which only widens when he gets to cruising down the aisles, and especially when we head to the meat department which is his favorite. He loves to stand holding onto the low edge of the case and stare up at the florescent lights. It's near impossible to pry him away, and we end up making several stops at various spots along the case between getting other groceries.

Often, fellow shoppers smile at us. Some will tell me what a good mother I am, or remark on the love I show Calvin as we embrace in the middle of the produce department or in the check-out lane. On a few occasions, strangers have even given us cash, which I try my best to refuse.

When we exited the store, Calvin still had his big goofy smile on his face. It made me think about how happy it makes Calvin just to hang out in the familiar grocery store with its colors and lights and shiny, crinkly packaging. It made me think of how happy it makes me to see him like that. It made me realize that I don't have to be in some exotic place for days, or climbing some mountain, or visiting a new city to feel true happiness. Rather, what matters is the simple, easy, mundane moment—whether rounding a bend in the car and looking back to see Calvin contentedly chewing on his macrame rabbit, his shoe or big toe, or five minutes with our butts parked at Simpson's Point, or a half hour in the grocery store standing mid-aisle—with my sweet, smiley, loving kid in my arms.

8.04.2023

setting records

In July, this kid set a new personal record by going three months without having any seizures! No doubt Calvin is benefiting from one of his two new-ish drugs, Xcopri, (the other being Briviact.) It does seem that having fewer seizures has helped him feel better overall; he is having fewer manic outbursts, wakes up content and goes to bed smiling when we hug and kiss him.

Amid fewer seizures, and therefore less anxiety and worry for us, we've been taking him to a few more places. On average, he has been more compliant about walking. We are seeing him smile more often—not just at bedtime—which warms my heart. Here he is walking at one of our favorite haunts, Simpson's Point, which we have visited by car probably thousands of times, particularly during the pandemic when Calvin did not go to school for fifteen months and was unable to access remote learning (because he is incapable.)

Now Calvin's brief and abbreviated summer school is already over, and so he is left with zero services for the entire month of August. That means we will be taking more car rides and walks and trips to the grocer. He's pretty game for it all, at least more than ever.

Thanks for all your love and support. Sorry I'm not writing as much these days. For now, suffice to say we're all doing well!

6.27.2023

good news

my days are still taken one at a time. days are long. time is short. sleep is thankfully less elusive than it used to be. and i have some good news ...

one of calvin's new drugs, xcopri, is helping him sleep better. it has also helped him to go sixty days without any seizures on the heels of a forty-eight-day seizure-free stint. xcopri has also allowed us to completely wean calvin off of the homemade thca cannabis oil i have been making and giving him for nearly ten years! i'm so grateful i was able to provide it for him for so long because it seemed to help his seizure control, but what a relief not to have to source the cannabis flower, buy it, get a liquor license to purchase and ship the 190-proof organic alcohol i use for extraction, make the oil, measure it and administer it!

calvin is on track to have just a fraction of the forty-two grand mal seizures he had last year. If he continues to be seizure-free on his current xcopri dose of 200 mgs, he will end the year with only seven grand mals and one focal seizure! That may be the fewest seizures he's had since first being diagnosed when he was two years old.

as calvin enjoys better sleep and longer stretches between seizures, he seems to be happier. he smiles more when we hug and kiss him. he seems slightly more compliant when we take him places. at school, they are having him wear a compression vest, which they say calms him. i'm grateful for every bit of this and so pleased i can share it with you!

besides all this good calvin-related news, my personal joy has been coming from near-daily running, taking photos, baking, and a bit of gardening. i would like to post to my blog and work on my memoir more, but i am trying not to "should" myself. i am simply hoping to find joy and some sense of freedom from calvin-related worries.

so, forgive me if you don't hear from me much these days. i'll try to keep checking in, and i'll try to write something that is more than simply an occassional news update.

be well, friends. xoxo

6.09.2023

maddi

5.22.2023

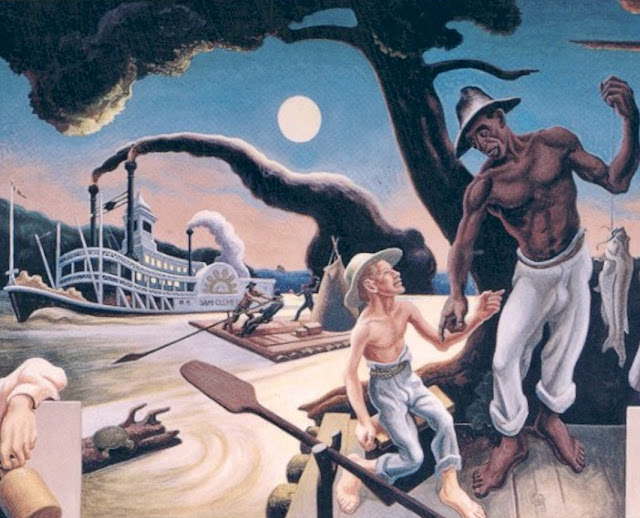

huck finn

From 2012

We

had the sky up there, all speckled with stars, and we used to lay on

our backs and look up at them, and discuss about whether they was made

or only just happened. Jim he allowed they was made, but I allowed they

happened; I judged it would have took too long to make so many. Jim said

the moon could ‘a’ laid them; well, that looked kind of reasonable, so I

didn’t say nothing against it, because I’ve seen a frog lay most as

many, so of course it could be done.

—Mark Twain's Huck, from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

In

recent years I’ve been taken with reading and rereading the classics

... Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great

Gatsby, Nabokov’s Lolita, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin,

Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. I love them all. This time through

Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, though, I am looking at the

characters’ exploits from a much different perspective than when I was a

youth.

The other day, after an entire day of wonderfully

backbreaking gardening, I washed off my dirt-smudged face, pulled on

some cowboy boots, donned my leather jacket and took off on a ride. She

started right up with the kind of meaty, gravely purr I’ve quickly come

to love. In some ways, driving my motorcycle feels liberating, like

riding a responsive, obedient horse, bringing her to a gallop with the

flick of a wrist—zero to fifty in no time flat.

Cool air rushed

up my sleeves as I meandered down Mere Point past impressive granite

shelves sprayed with heather and flox, trees caked with lichen, and some

apricot-colored buds dotting a pine canopy. The air smelled fresh but

of nothing else. Near the end of the road the sky opened up as did the

land, and I could see across a clear-cut parcel to the water. At the

boat launch I cut the engine and sat quietly gazing across the inlet.

Once

the residual buzz of the motor gave way, my senses drown in the sounds

of chirping birds, waves lapping the shore, and the sun on my face. At

the end of a long pier, two lovers embraced as if they were alone in the

world. The pier, with its weathered wooden slats, reminded me of the

raft that Huck Finn and Jim floated down the Mississippi river. I

thought about how their fantastic journey was as much about forging

their companionship as it was about their physical adventure.

I

studied the lovers—her pale arms contrasting with his black hair and

shirt, their legs disappearing over the side of the pier, perhaps

barefoot as I imagined Huck and Jim to be, dipping their toes into the

water like I'd done before. The lovers remained as I shut my eyes and

imagined Huck and Jim floating, tossing twigs into muddy water, fishing

for their breakfast, building campfires, telling tales, getting to know

each other's realities which were so very different and yet so perfectly

matched, not unlike some fathers and sons.

I reminisced about

some of my escapades as a young person and the curious friendships I’ve

formed over the years. Then I considered, as I’m known to do, that my

boy Calvin will never enjoy the luxury of getting into the minds and

thoughts of other folks. And then a stream of consciousness overcame me .

. .

he’ll never fish from a pier with his dad or build a

campfire or sleep by himself under the stars or embrace a lover or tell a

story or ride a motorcycle or captain a raft or talk with a friend

about the origin of stars or read a book or write a word or cook a meal

over hot coals and a flame or swim like a fish in a river or catch a

firefly or gallop a horse or forge a friendship like Huck and Jim or the

lovers or most anyone in the world or write a work like Samuel Clemens

might have thought of doing when he was Calvin’s age.

Then I

started up the engine and continued my own little escape up the road not

far from the water's edge and under the invisible stars.

5.15.2023

mother's day

Mother's Day cards and gifts will fade or be thrown out, get packed up into some anonymous cardboard box in the basement or be lost in moves. Flowers will wither, balloons will deflate or sail away, plants will one day die. But these memories I have cuddling with Calvin will last forever, if not always in my mind, then in my heart, in the marrow of my bones, and mean more than any bit of material evidence I could glean from a son on Mother’s Day.

At least that is what I tell myself.

4.30.2023

joy of sport

i began swimming competitively at the age of six. in high school, i earned all-american honors as the lead in the washington state champion 400 freestyle relay. later, i was voted most inspirational and, as a senior, team captain. i then went on to compete for the university of washington (NCAA division I) and central washington university (NAIA) where i earned academic all-american honors and was voted team captain the year my team won the national championship.

|

| caught in the downpour! |

4.21.2023

catching a breather

run—away, to, from, for something. feel alive. free. breathe. fly. skate. soar. smile. wave. weep. see—oceans, vistas, trees, owls, ochre leaves. smell hay, clover, salt, goats, sea. anticipate. hope. vibrate. sting. ache. forget. dream.

i've been trying to do all the those essential things, to take my own advice so i can do more than merely survive, but so i can thrive amid caring for someone with so many basic and dire needs as my son calvin.

but in reality, calvin, his caregiving, his advocacy, have always gotten in the way, which is why i haven't written in a while. i'm really sorry! i've been dealing with reams of calvin-related paperwork, a struggle with his school district over the problematic shift and significant cutback of his summer school, his ongoing doctor's appointments, blood draws, and diagnostic imaging meant to follow up on his previously broken hip, his pneumonia, his gallstone(s), and the placement of a stent in his pancreatic duct during an Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedure last month. but i finally found the time to catch a breather and write.

since calvin's ERCP, he has been doing pretty well. he hasn't had waves of that excruciating pain that landed us in the hospital on New Year's Eve, nor has he had a seizure in forty-one days—his second-longest stint in what is probably close to a decade! he seems to mostly be in good spirits, and is sleeping fairly well. he takes moderate doses of two newer anti-seizure drugs, xcopri and briviact, and i have cut his thca cannabis oil dose in half without any problems.

so, too, calvin's receptive communication seems to be improving. his ability to "tell" us what he wants (a bath, juice, to go outside, to get on the bus or go for a car ride) is also better. though it's not easy or fun, i'm focusing more on his profound autism, and looking for ways in which we can work on improving his problematic behaviors to make it easier for everyone to take care of him (i'd like to simplify his treatment).

as for my own personal non-calvin-centric endeavors, i've been running a lot and training for my first ten-mile road race, which is this sunday in portland, maine. i'm hoping for good things. i'm hoping it doesn't rain, though that isn't looking very promising. i'm hoping for a fast time. i'm hoping to see friends and meet new people. running has been a savior and helps make my life feel more okay.

and so, since i often feel like i need a break, a respite, a lifesaver, i'll hopefully be able to keep running and smiling and waving and weeping and, as often as possible, dip into nature to soak up all it has to offer, forget all the rest, and continue to hope, vibrate, sting, ache, forget, dream.

3.11.2023

weekend update

At 3:30 this morning, Calvin had his first seizure in three weeks. Since beginning the drug, Xcopri, in November of 2021, he has been enjoying "longer" stints, including one seizure-free span of forty-five days. We haven't seen any focal seizures for over a year. So, despite a trip to the emergency room last April when he broke his hip at school, then having to undergo surgery to install three metal screws to fix it, and despite another trip to the emergency room on New Year's Eve for an excruciating case of cholelithiasis (gallstones), plus gastroenteritis and aspiration pneumonia, Calvin looks to be heading for his best seizure control in years.

As far as the gallstones go, Calvin had an endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) procedure at the hospital on March 1st. After waiting for three hours in a type of holding cell, he again went under general anesthesia. The procedure, which involves the insertion of a scope into his esophagus, went fine, though the physician did not find the gallstone that was allegedly stuck in his common bile duct. Instead, what the doc found was "sludge"—bits of stones and/or fat, perhaps—which he cleared out. He also widened the sphincter where Calvin's common bile duct enters the duodenum, so that future stones can pass more easily into the intestine and are less likely to block the pancreatic duct, which can result in serious, sometimes lethal, consequences.

So, I guess one could say that the ERCP was successful. Calvin is eating well again and thankfully has not exhibited the kind of pain we saw him experience in December and January.

So, that's the update, folks, except to add that hopefully Calvin's seizure this morning will turn out to be a one-off.

Thank you for your thoughtfulness and well wishes. As always, they mean the world.

2.28.2023

hope and trepidation

Tomorrow morning, Calvin and I will finally make our way to Maine Medical Center for his endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) meant primarily to remove at least one gallstone that is stuck in his common bile duct and which probably caused the excruciating waves of pain and elevated pancreatic enzyme that landed him in the emergency room on New Year's Eve. Calvin has likely needed this procedure for weeks if not months, but it has taken this long to get it on the books because—although every radiologist who read Calvin's CT scans and sonograms reported seeing at least one decent-sized gallstone—one of Calvin's providers wasn't convinced. Eventually, the procedure was scheduled, but then Calvin brought Covid home, and we had to postpone the operation a week.

The ERCP is not technically a surgery. It is an endoscopic procedure during which Calvin must undergo general anesthesia. The gastroenterologist—one of only two in Maine who has the skill to perform this operation—will insert a scope through Calvin's mouth into his esophagus to look for ulcers, etc., then go on to remove the problematic gallstone, perhaps having to widen the common bile duct so it passes more easily.

This will be Calvin's fourth time under general anesthesia. In the past, he has faired well, but the risk of dangerous complications is far worse for someone like him who is neurologically compromised and prone to getting pneumonia which, by the way, he was diagnosed with on New Year's Day. The last time Calvin had to have general anesthesia was last April during surgery for the hip he broke at school (a clean break at the base of the femoral head) when his aides let him walk around by himself and attempt to sit in a chair, which he most regrettably though not surprisingly missed (his vision and coordination are not good).

It is hard to put into words how gut-wrenching and nerve-racking it feels to watch your sweet, nonverbal, cognitively impaired child be wheeled down a hallway with a bunch of strangers into an even stranger room (operating rooms are cold, chrome, sterile places) without any understanding of what is about to happen or why, and without mom or dad by his side to comfort him. To say the experience is worrisome is an understatement. It is the cause of great trepidation.

And so, using the gastroenterologist's patient portal, I wrote to the physician who will be performing the ERCP:

"can i stay with calvin until he goes under general anesthesia?"

The doc replied within minutes, "yes. you can stay with him."

I breathed a sigh of (some) relief.

With any luck, the procedure will go off without any hitches, Calvin will make it safely out from under the anesthesia without aspirating or suffering from too much irritability, and we'll be home sometime tomorrow late afternoon or early evening. Hopefully, Calvin will get some immediate relief from the prolonged pain and discomfort that this gallstone has likely caused him and, hopefully, he'll be protected, at least for a while, from the dangerous sometimes lethal effects that gallstones can cause.

Sadly, Michael cannot join us because it has not yet been ten days (hospital protocol) since his Covid diagnosis, and because he'd miss another day of teaching; I urged him into staying behind. Thankfully, one of my besties, Barbara, is going to drive me and Calvin to the hospital in Portland, and another bestie, Matty, will shuttle us back so I can attend to Calvin's needs on the drive home.

Until then, cross your fingers and toes.

|

| Michael, in white, escorting Calvin as far as allowed before Calvin's hip surgery last April. |

2.14.2023

reason and being, purpose and meaning

I watch as a boy of five or six falls off of his bicycle. Somewhat remarkably, he lands squarely on his hands; his feet quickly follow. Having escaped injury, he rises and claps triumphantly, then begins to do a goofy, self-styled boogie, which is perfectly annoying to me. The caption on the video reads, "This should be your reaction when life challenges you."

For starters, I'm not a fan of the word, "should." I try not to "should" anyone, including myself. The rest of my cynical response to the video was—like most things—informed by my profoundly disabled, nonverbal, seizure-prone son. Calvin had just come off of a very shitty few weeks which began with back-to-back grand mal seizures, followed by waves of excruciating pain of unknown origin, the likes of which reminded me of Hollywood torture scenes. Ultimately, Calvin landed in the emergency room on New Year's Eve with an agonizing case of viral gastroenteritis and/or a problematic gallstone, which—after reviewing X-rays, a CT scan, and several blood draws taken at ungodly hours—the doctor said had likely caused the aspiration pneumonia in Calvin's left lung. We were released from the ER the following morning, and though I was relieved to be out of there, I didn't feel like dancing a jig; I felt only grateful that it seemed we may have dodged the latest bullet in Calvin's lifelong barrage of them.

Calvin reminds me daily that not everyone is equipped or inclined to celebrate or give ourselves high fives after life's nasty pitfalls, even if we eventually land on our feet. Sometimes, some of us come away from challenge and hardship feeling confusion, guilt, insecurity, anger, angst, resentment, exasperation, despair. My first reaction to the dancing boy was to acknowledge that not everyone is sailing along in life in the first place, or lucky enough to avoid misfortune such as hunger, war, poverty, displacement, abuse, injustice, depression, the death of a child, or one born to a life of profound physical and cognitive limitations and miseries, like Calvin. Call me a Debbie Downer for criticizing what some might consider a harmless, light-hearted video. I mean, I get the gist, and I'm generally an upbeat optimist who sometimes even welcomes challenge, however, I look at certain subjects through a more serious lens than others.

The video also reminded me of the countless times people have told me that everything happens for a reason. Though the sentiment is meant to be comforting, I generally respond by disagreeing, then go on to explain my preference for the notion of gleaning great purpose and meaning from life's hardships (a practice which can also be elusive to some) as opposed to there being some mysterious reason baked into every awful thing that happens. If I probe, some folks claim that bad things happen to teach us lessons. I usually respond by telling them I am not worthy of my son's suffering. Others say we can't know the reasons for mishaps and tragedies, but that God has a plan. I'm always left wondering: if there is an omnipotent god with a plan for everything, why does it so often include godawful misery, and how is that not deeply disturbing if not unthinkable? Would an all-powerful god orchestrate every little scrape and bruise I get and/or the immense suffering my son endures? Does God stage and sanction starvation, war, genocide? What kind of god has a reason—and what in God's name could that reason be—for the torture of "his" beloved children at the hands of others, or from excruciating illnesses? And if God isn't responsible for orchestrating horrors such as mass shootings, catastrophic fires, floods and earthquakes, then why doesn't "he" rescue us from suffering? Even we puny humans will do virtually anything in our power to save our children from pain. Why doesn't God? And if there is a reason for everything, what does that say about the notion of free will? Lastly, some people say God is testing us, and my immediate response is to ask: for what purpose? To what end? Is God conducting some test of fidelity, and if so, what deep conceit does that reveal? And what would be the point of testing us, knowing we are impossibly fallible beings?

I've found myself ruminating over the bicycle-boy video and related conversations for weeks, and I'm taken back to my childhood. Despite being raised Catholic, I began doubting the existence of a merciful, omnipotent god when my best friend's two-year-old sister nearly drowned in their nearby swimming pool. I had been outside when I heard the dog barking and the mother discover her baby girl lifeless in the water. I had never heard a grieving human shriek and howl so animalistically. She fished her daughter out of the pool and resuscitated her. The child survived, but was in a coma for at least a week and emerged from it no longer a toddler, having lost every one of her acquired skills. Her recovery, while not utterly complete, took years. I'm surprised her mother survived the ordeal, and I wondered if she felt as if God were punishing her for some petty transgression. It didn't make sense to me that a merciful god would allow any of "his" flock to suffer and grieve so deeply. It all seems so utterly senseless.

In continuing to ponder the theory that everything happens for a reason, I wondered if maybe that reason is merely that we exist. Perhaps it's as plain and simple as that: we exist, and therefore things happen to us. It seems reasonable that all things great and small, as in nature—rain, sunshine, hurricanes, earthquakes, moss growing on trees—just occur without any divine reason. In other words, as the saying goes, shit just happens. It makes sense to me—and frankly is far more comforting than the notion of a god with a secret plan sitting idly by while we are tormented—that our every move isn't governed, decided, judged and orchestrated by a god. And, too, maybe overcoming life's nasty challenges and curveballs isn't always reason for smug celebration, but rather, a time for reflection, gratitude and humility, especially considering so many of our fellow beings, through no fault of their own, live in a world of misery.

|

| Photo by Michael Kolster, August 2021 |

2.07.2023

nineteen

Nineteen years ago today—six weeks before his due date, two weeks after a sonogram revealed an alarming absence of white matter in his brain, and a week before a scheduled cesarean at Boston's Children's Hospital—Calvin came into the world during an emergency cesarean at Portland's Maine Medical Center—in the middle of an ice storm. I guess that's how he rolls.