From 2012

We

had the sky up there, all speckled with stars, and we used to lay on

our backs and look up at them, and discuss about whether they was made

or only just happened. Jim he allowed they was made, but I allowed they

happened; I judged it would have took too long to make so many. Jim said

the moon could ‘a’ laid them; well, that looked kind of reasonable, so I

didn’t say nothing against it, because I’ve seen a frog lay most as

many, so of course it could be done.

—Mark Twain's Huck, from The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn

In

recent years I’ve been taken with reading and rereading the classics

... Hemingway’s The Sun Also Rises, F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great

Gatsby, Nabokov’s Lolita, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s Uncle Tom’s Cabin,

Salinger’s The Catcher in the Rye. I love them all. This time through

Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn, though, I am looking at the

characters’ exploits from a much different perspective than when I was a

youth.

The other day, after an entire day of wonderfully

backbreaking gardening, I washed off my dirt-smudged face, pulled on

some cowboy boots, donned my leather jacket and took off on a ride. She

started right up with the kind of meaty, gravely purr I’ve quickly come

to love. In some ways, driving my motorcycle feels liberating, like

riding a responsive, obedient horse, bringing her to a gallop with the

flick of a wrist—zero to fifty in no time flat.

Cool air rushed

up my sleeves as I meandered down Mere Point past impressive granite

shelves sprayed with heather and flox, trees caked with lichen, and some

apricot-colored buds dotting a pine canopy. The air smelled fresh but

of nothing else. Near the end of the road the sky opened up as did the

land, and I could see across a clear-cut parcel to the water. At the

boat launch I cut the engine and sat quietly gazing across the inlet.

Once

the residual buzz of the motor gave way, my senses drown in the sounds

of chirping birds, waves lapping the shore, and the sun on my face. At

the end of a long pier, two lovers embraced as if they were alone in the

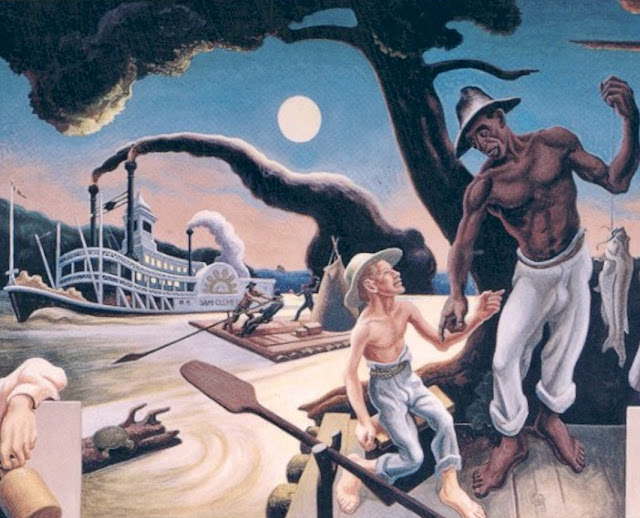

world. The pier, with its weathered wooden slats, reminded me of the

raft that Huck Finn and Jim floated down the Mississippi river. I

thought about how their fantastic journey was as much about forging

their companionship as it was about their physical adventure.

I

studied the lovers—her pale arms contrasting with his black hair and

shirt, their legs disappearing over the side of the pier, perhaps

barefoot as I imagined Huck and Jim to be, dipping their toes into the

water like I'd done before. The lovers remained as I shut my eyes and

imagined Huck and Jim floating, tossing twigs into muddy water, fishing

for their breakfast, building campfires, telling tales, getting to know

each other's realities which were so very different and yet so perfectly

matched, not unlike some fathers and sons.

I reminisced about

some of my escapades as a young person and the curious friendships I’ve

formed over the years. Then I considered, as I’m known to do, that my

boy Calvin will never enjoy the luxury of getting into the minds and

thoughts of other folks. And then a stream of consciousness overcame me .

. .

he’ll never fish from a pier with his dad or build a

campfire or sleep by himself under the stars or embrace a lover or tell a

story or ride a motorcycle or captain a raft or talk with a friend

about the origin of stars or read a book or write a word or cook a meal

over hot coals and a flame or swim like a fish in a river or catch a

firefly or gallop a horse or forge a friendship like Huck and Jim or the

lovers or most anyone in the world or write a work like Samuel Clemens

might have thought of doing when he was Calvin’s age.

Then I

started up the engine and continued my own little escape up the road not

far from the water's edge and under the invisible stars.