I grew up in a family of swimmers. One of my brothers swam his first race as a wiry four year old. I joined my siblings on our summer league team when I was six. At nine I started competing year round. At fourteen, still in junior high school, two friends and I earned varsity letters on the high school team. That was the year I started double workouts—dragging myself to high school practice in the predawn hours and then draining myself during the two-hour afternoon AAU workouts.

After my senior year in high school, having peaked as an All-American in my sophomore year, I was pretty burnt out. But a friend convinced me to join my college team, the University of Washington Huskies, a member of the Pac 10 conference.

I was one of the slowest swimmers, my heart not really in it. During the long distance sets I’d let myself get passed by a few of the six or seven others that shared the lane. I was ashamed for being a weeny and for not putting in my best effort. I just didn’t really care, and besides, it was painful, monotonous and exhausting and I’d already spent more than half of my life doing it, and for what? But I had committed, so I stuck with it. The other swimmers probably figured I was a dud, but I held my own in the sprints, though didn’t achieved what I could have, lacking the spirit and inspiration I had enjoyed back in high school.

During the two-week winter break our team continued to practice doubles. I spent nights at home with my family, but six days a week I drove across the lake to the Seattle campus for our two-hour morning practices. I retired to my empty dorm for lunchtime naps, then returned for our two-hour afternoon practices before heading home to eat dinner. It was a grueling, lonely recess. The last day of winter break training—the hardest—we swam a total of 15,000 yards, equivalent to nine miles—in one day. We were all spent, broken, wasted.

As a junior I transferred to a smaller university and relished two successful years with a more laid-back team. I finished my senior year with several all-time best performances as well as All-American and Team Captain titles. That year our proud men’s and women’s teams won the NAIA championship.

Sometimes, though, it all seemed so senseless, to run my body into the ground in hopes of shaving a few seconds—or tenths of a second—off of my best race. But after graduating college I came to realize that the most important lessons I’d ever learned were from a lifetime of swimming. It took hard work, dedication, patience, commitment and focus. I’d learned how to win humbly and how to lose with dignity. I perfected strategy, teamwork and goal setting. We swimmers saw each other practically bare-naked, emerging from sleep grumpy with no makeup and ratty bed-heads, yet none of that mattered. We were a team, all in the same boat, lifting each other up, pulling for one another.

In some ways my most important discovery from swimming was learning how strong and capable I really was, not just as an individual, but as a female, and not just physically, but emotionally. I pushed myself beyond the brink of exhaustion to the point of nausea and tears because it hurt so much, I beat the unforgiving clock time after time, I repeatedly bench-pressed more than the weight of my body.

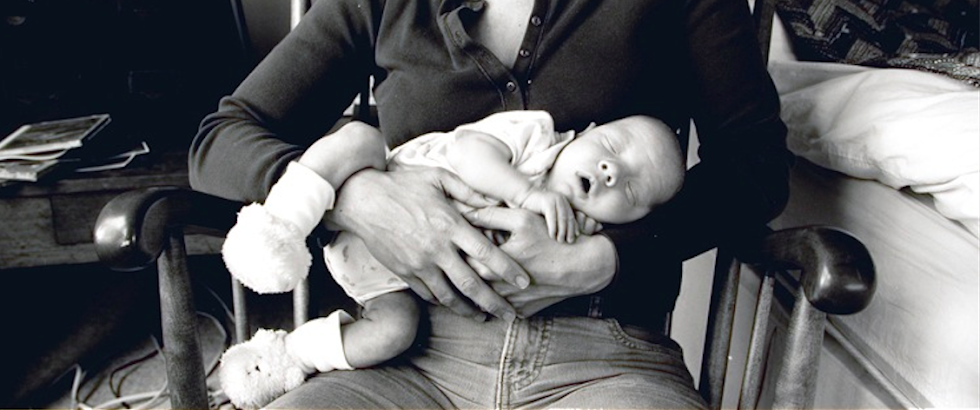

The lessons I've learned from swimming have helped equip me for the job of raising my son Calvin, which is probably the hardest thing I’ve had to do in life. I can carry his slack weight on my hip with one arm, I painstakingly strategize his complicated health plan, I assert myself as his vicious advocate, I utilize all of my resources for the goal of helping him to reach his full potential, and I never give up no matter how much it hurts.

So I suppose, although I don’t necessarily have fond memories of the pain, I should be thankful for all those excruciating sets of ten two-hundreds and the thousands of sit-ups that my coaches made me do.

|

| Summer 1970 |