calvin's story

12.24.2022

riches

12.08.2022

knock on wood

Yesterday, things were not looking good: outside the wind and rain were raging; Calvin had a snotty nose and was running a low-grade fever; the full moon was on the rise. The good news was that it had been twenty-five days since his last grand mal seizure.

Michael and I crawled into bed just before seven—a record early one for us (it's our version of sleeping in.) I read a few, short chapters of Elizabeth Strout's new novel, Lucy By the Sea, before drifting off to sleep. It was not quite seven-thirty when I took a last peek at the clock.

Ten-and-a-half hours later, I woke up to Calvin making his groggy morning coos. He hadn't had a seizure! I was so stoked.

So, Calvin, who has been titrating up on a new drug, Xcopri (aka cenobemate), since November a year ago has had just three seizures—albeit all within twenty-six hours of each other—in seventy days. That's almost a personal best. He's on track to have just over half as many grand mal seizures this year as last (about 38 compared with 72 in 2021) and he hasn't had any obvious focal seizures since last February compared with over twenty last year. I owe this huge improvement to the Xcopri. I should also mention that, for weeks now, I haven't felt like I've had to give him any extra prophylactic doses of my homemade THCA cannabis oil, something I was doing almost daily a couple of months ago.

My hope is that Calvin can soon get to a place where we can either switch his Keppra to its cousin, Briviact, which, I'm told, is just as efficacious and has fewer behavioral side effects, or we can wean him from the Keppra all-together (because it doesn't seem like it does jack shit. One day, I'd also like to wean him from the cannabis oil so that he is getting less drug treatment. I'm hoping his body doesn't habituate to the Xcopri. I'm holding onto hope that it might be the silver bullet Michael says doesn't exist. Eternal optimist, I am.

Having said all that, tonight Calvin is still sick and stuffy and running a low-grade fever. I just put him to bed. If he makes it through tonight without a seizure, it'll feel like a miracle. Cross your fingers. Knock on wood.

12.02.2022

back in time

"Yes. More than anything in the world," he replies, as he looks at me with intent.

A bit incredulously, I follow with, "Even Calvin?"

"Yes," my husband answers, "but he's catching up."

The expression I give lets him know I wonder what he means.

"He's becoming more lovable," he says.

"Like when he was a baby," I add, "when he was feeling good ... he was all happy and lovable. It's the drugs that have fucked him up."

After a pause, I go on to say:

"Some doctors are assholes," thinking about the bad ones—the one who needlessly prescribed Calvin's first benzodiazepine and the ones who prescribed extremely high doses of too many drugs—sometimes several at once—that didn't work and that fucked him up, caused him to be and remain so impossibly restless.

Michael nods his head.

"I wish we could go back in time." I say, wishing I knew—and could have employed—then what I know now.

11.24.2022

thanksgivings

pink dawn. stove top espresso with warm milk waiting for me just like every morning. the smell of freshly-baked cheese bread. a slice of it warm with butter. great-feeling, sub-freezing pennellville 10k. black-camo and leopard-print leggings. puffer jackets and running gloves. day-glo yellow running shoes from joanie. calm water. day eleven seizure-free for calvin. hot shower. danish coffee cake from wisconsin. a fire in the stove all day long. smiling child. funny husband. cozy home. stained-glass window. quiet streets. the structure of winter trees. moss and lichen. red berry. tufts of cat tail blowing in the wind. pumpkin and pecan pie. panoramas. old friends and pandemic ones. running for miles in the wide open. the freedom it gives me. running with smellie on the trails. seizure-free child, at least for now. candle light. lilies in a blue vase. michael's students coming over for a thanksgiving meal. herbed, spatchcocked turkey. fresh green bean casserole with fried onions. garlic mashers. honey sherry shallot carrots. sunlight through trees and old wavy-glass windows. music on a kick-ass stereo. dancing like a maniac in the kitchen (makes michael smile and laugh.) gigondas. a bit of bourbon on the rocks. wicked-smart and hilarious neighbors. gatherings. laughter. friendship. drives on the back roads. gratitude galore.

11.13.2022

seize, grieve, repeat

11.03.2022

holding onto hope

i'm holding onto hope ...

hope that calvin can continue his seizure-free days past thirty-six. hope that somehow we can get him—once and for all—off of the bloody keppra. hope that his body will one day settle into something approaching calm. hope that he isn't feeling pain, hope that he stays well. hope that eventually, within our lifetimes, someone will find a cure. hope that at some point i don't ever again have to watch him seize.

i'm holding onto hope ...

hope that i can continue to run on the trails and roads, to feel its freedom, the sun on my face, the wind through my hair and the sound of it through the treetops. hope that i stay healthy and fit for many more years. that i remain young at heart (though that isn't really a worry.) that i remain injury free. that i can keep taking care of calvin, at least for the time being.

i'm holding onto hope ...

hope that calvin's school goes forward to be a safe and welcoming place where his typical peers continue to gain insights from his presence and energy. hope that more people in this world and nation begin to value difference and diversity. hope that young people keep learning the truth about this nation's full and true history. hope that everyone can get a bit away from their gadgets and, instead, get back to communing with nature.

i'm holding onto hope ...

hope that women won't lose the legal right to be equal citizens in this nation. that people can agree that healthcare is a goddamn human right for everyone. hope that the separation of church and state holds (at least to the extent it does.) that more and more people vote, and are not burdened by difficulties or dangers accessing the polls. that the election is free and fair. that people honor the outcome. that people stop believing the lies they are being told about a so-called stolen election. that extremists and liars lose. that violence doesn't rise up, but if it does, that it is quickly quelled. that democracy holds.

i'm holding onto hope ...

that one day leaders, and others, of this beautiful world will put aside their egos, their fetishes, their power lust, their deceit, their bombs, their guns, their crowns and swords.

10.14.2022

hell and angels

i don't believe in religion or in its hell or angels. to me, that hell is an absurd, fantastical, primitive invention, a relic of the dark ages. but hell on earth is real. i know, because it exists in the misery of my kid, in the pain and panic attacks he has that sometimes last for hours and deprive everyone of sleep. it's in the way he thrashes, cries and writhes in bed. it's in the agony and sadness etched into his soft forehead. it's in the way that so few things help my sweet kid when he's like this.

my perdition is in witnessing, in my helplessness and incomprehension, my inability to exactly understand the nature of his hurting, the meaning of his expressions. he has no words, only coos or hums. at hellish times, he shrieks and moans. it's this mother's agony to observe.

so, too, i feel the punishment of eighteen and a half years of "raising" an infant-toddler-teen. it's a job that doesn't come with vacations or weekends. all too often it is tedious and grueling. it requires i be on duty, or on call, around the clock every day of every month of every year. to keep him safe and warm and clothed, clean and dry and fed and loved. to keep him out of harm's way like any parent would. to comfort him when he's out of sorts. to give him medicine even when i can't know for sure his misery's source.

while running the other day, i heard a car skid to a stop. my heart skipped a beat thinking it was my kid—the rubber squealed as if it were his seizure-shriek. but it was just the sounds of the street. years ago, when we often called 911 for calvin's stubborn fits—one so long we thought his body would give out—i used to run after ambulances. while walking the dog on campus, i'd sometimes hear sirens screaming past. i feared they were headed to our house for my boy. i'd chase them till they'd turn down different streets. it was a godawful—hellish—frightening, worrying feeling.

no amount of writing can sufficiently describe how heart-wrenchingly difficult this kind of caregiving is. this witnessing of my child's suffering. the feelings of guilt rising from punishing frustrations born from lack of sleep, getting smacked by his errant fingers and fists, listening to his tiresome and irritating bleating, coping with his poopy diapers and sopping bibs, watching him repeatedly seize. the hell i feel is in the most of it. what's the worst, though, is his frequent misery. a kind of hades i really hate, and from which it seems there's no escape.

and so, no, i don't believe in god's hell or angels. but if there were angels, my precious calvin—with his impish grin, little muscles, strong embraces, smooth skin, huge eyes, cute dimples, ecstatic smile when we kiss him, his deep-down goodness and sweet disposition (when he's feeling well)—would hands down take the cake.

10.07.2022

anniversary

all kinds of mothers, fathers, doctors, nurses, restaurateurs, therapists, ice cream scoopers, bloggers, children, ed-techs, in-laws, sales reps, grocery store clerks, photographers, chefs, brothers, teachers, flight attendants, runners, city councilors, dietitians, case managers, receptionists, kindred spirits, painters, octogenarians, presidents, ed-techs, bar tenders, cooks, bus drivers, radio talk show hosts, chaplains, lawyers, actors, neuro-ophthalmologists, contractors, professors, nurse practitioners, marathoners, deans, physical therapists, grandmas, grandpas, farmers, farmhands, coaches, nieces, nephews, priests, college friends and their spouses, athletes, bowl-turners, aunts, uncles, cousins, principles, headmasters, musicians, retirees, servers, brewers, hair stylists, writers,s founders, weeders, orthotists, superintendents, directors, students, ex-students, curators, sisters, poets, producers, carpenters, baristas, CNAs, actresses, technicians, former coworkers, contractors, designers, business owners, candidates, librarians, congresswomen, critics, high school buddies, neighbors, longtime friends of the family, occupational therapists, speech and language pathologists, pharmacists and their staff, hospital staff, phlebotomists, neurobiologists, film makers, celebrities, readers and kind strangers.

Thank you for reading and sharing and connecting and caring. You’ve all done something—whether unwittingly or not—to make our lives richer, more comfortable, happier, better, and for that I owe you each a debt of gratitude.

10.03.2022

blind luck

The sound Calvin makes when he has a grand mal seizure is no sound a parent wants to hear coming from their child, nor anyone for that matter. It's blood-curdling. Sometimes it's strident, a bit like a barking dog or seal, and at others it sounds like someone being murdered. The screech that ripped me out of sleep Wednesday morning was doubly loud, long and alarming for some reason. To add insult to injury, it came on the heels of last Monday morning's grand mal.

It's a sinking feeling watching your child seize, especially when there's really not much to do save administering emergency medications, which have their own slew of troubling side effects, though luckily aren't usually necessary for Calvin since for years his seizures have stopped on their own. The clusters, however, are harder to control.

And so, to avoid subsequent seizures, when the seizure was over I incrementally syringed two milliliters of my homemade THCA cannabis oil into the pocket of Calvin's cheek and watched him drift back to sleep. Then, to monitor his breathing, I crawled in next to him—head to toe now that he's bigger—held his little foot in my hand, and my brain went to work on the days' events.

I thought about how last Tuesday authorities found the body of fourteen-year-old Theo Ferrara, the boy who went missing in the next town over nearly two weeks ago, and about whom I mentioned in my last post. His body was found in the waters of Maquoit Bay near Bunganuc Point not far from where I drive with frequency, and just downstream from where I took this photo.

Considering the lightweight clothing Theo had been wearing when he was last seen—a windbreaker, t-shirt, shorts and flip-flops—the chilly nights dipping into the forties had added to my worry. Since his disappearance, I'd been going to bed thinking of him and hoping he'd turn up safe and sound somewhere. The news is tragic, and authorities won't know the circumstances of his death for weeks.

To aggravate the tragedy of Theo's death, on social media earlier last week parents were posting pictures of their children in celebration of National Daughters and Sons days. While I love, am grateful for, and am proud of my sweet boy Calvin, the feelings the photographs evoked are bittersweet because too many of my friends' precious children—Lily, Rose, Rainier, Jennifer, Will, Tyler, August, Kelli, Martin, Mikki, Mike, Kevin, Ronan, Charlotte, Arnd, Michael, Elisif, Melissa, Matt, Cyndimae, Katie, Christina Taylor, Finnegan—left this earth far too soon. Still others may have tried to have had children but couldn't.

9.26.2022

lost boys

I was going to write about why I haven't been writing much (instead, busy with running, some autumn gardening, taking care of a recently-sick Calvin, and doing online modules to complete my DSP (direct support provider) "training" so that I can begin being paid a little for taking care of Calvin. I was going to write about the fact that, on a moderate dose (100 mgs) of Calvin's newest drug, Xcopri (cenobamate), he's been going longer between seizures (thus having fewer), and that he didn't have a fever or a febrile seizure after last Friday's Covid booster. I was going to mention that he hasn't had any focal seizures since February, and that, overall, his behavior is better.

I was going to write about our near-perfect trip to the Cumberland County Fair yesterday where, under hazy, lavender-ish skies, Calvin did some amazing, albeit brief, stints walking by himself (too good to be true? we wondered aloud) down and back through a barn of draft horses and even a bit further. I was going to write about how straight and stable he sat at a red picnic table drinking from his sippy cup, that he enjoyed bites of warm, cinnamon-sugar donut, that all day long he signed "eat" very well, putting his finger to his mouth when he wanted more.

But, halfway through our time at the fair, when the crowds began to gather choking the pathways, and the midway rides ignited their noisy motors, and the hot sun began to filter through a bit too strong, Calvin's relative well-being seemed to go south. His intermittent walking deteriorated, so we put him back into his stroller. His skin felt hot. His face went pale. He began to perseverate, elbows crooked and waving, knitting his fingers. On the drive home, he batted and grabbed for me incessantly as if to be saved from something.

Then last night came the perfect storm—the new moon, a drop in the barometric pressure, perhaps a semi-latent affect from Friday's Covid booster, the sky opening up to unleash one of the hardest downpours I've heard since moving here—and at 2:45 this morning, Calvin had a grand mal seizure. It had been fifteen days since the last one. This time, when the fit was over, I gave Calvin twice as much of my homemade THCA cannabis oil as I usually do, hoping to prevent a second one from striking like they often do. Thankfully, it seemed to work.

As I laid in bed next to my boy in the pitch black of his room, I thought about the day's events and the looks Calvin got from strangers—some kind, others curious or suspicious, perhaps even put-off. I thought about the rides I would've liked to have taken him on, the animals I wish I knew if he saw and wish he could enjoy petting, the contests I wish he could've entered if he wanted to, the fact that, in ways, Michael and I wish we could've been at the fair without him.

As Calvin slept, at times arching, I thought about our ride home through parts of Freeport, Maine, where good neighbors and authorities were and are actively searching for a skinny fourteen-year-old boy named Theo who went missing four days ago wearing shorts and flip flops as nights dip into the forties and fifties. I wondered what happened to him. Was he snatched up by a nefarious actor? Did he fall into a hole or into frigid waters? Was he bullied into a state of anxiety, depression or some sort of submission? Did he end his own life? Was he trying to escape something or someone?

Then, I thought about the bluegrass concert given at my friends' gorgeous farm last Friday night in memory of their young and precious son, Finnegan, who died in a kayaking accident last November. So many amazing and loving people gathered together to make food, music, and memories in honor of a beautiful boy—at nearly 24, a young man, really—who was lost far too soon. I felt grateful to have been able to be there, at least long enough to give and get some hugs, to visit with beloveds a bit, and to remember my young friend, Finnegan, for the incredible human being he was.

In thinking about Theo and Finnegan, I considered the grief I feel over my own lost boy. I often wonder what would have become of Calvin—or what he would have become—if he hadn't been born missing most of the white matter in his brain. I mourn the loss of a boy who is flesh and blood sitting right in front of me—the loss of his artistic, athletic, academic, physical, philosophical, humanitarian potential. The loss of seeing him make friends and meet new people, and of us becoming their close friends, too. The loss of seeing him fall in love. The loss of the potential of having a growing relationship with our adult child. The loss of possibly having a grandchild or two to dote on.

Then, I think about my blog and memoir in progress and how I'd never have started writing them if not for my boy. Perhaps I wouldn't be quite so charmed by gardening if I didn't feel the need to shape nature since I can't control my son's regrettable disabilities and miserable afflictions. Maybe I'd never have started running (again) if not for need of an escape from a hard and restricted life of mothering an impossible infant-toddler-teen. Maybe I'd never have embarked on my pandemic back roads travels, which have bore new friendships, sparked a love for taking copious panoramic photographs, caused me to reflect so deeply on life and the mundane. These amazing endeavors I'd likely never have chanced upon if not for Calvin.

And though it's no consolation, my lost boy and what he has brought to me and to others is so worthwhile, and worth pondering.

9.16.2022

universal beauty, unconditional love

If my nonverbal, incontinent, legally blind, unconditionally-loving son Calvin has (unwittingly) taught me anything, it is to be grateful. That might seem counterintuitive considering our sorry situation, but I've come to understand that mindfulness and gratitude are two practices that help get me through the bruising parenting of a cognitively and physically disabled child who has a chronic condition as relentless and unforgiving as epilepsy. Gratitude and mindfulness help keep me grounded while at the same time distract me from getting stuck on the troubling aspects of life concerning my son.

Last Saturday night was a rough one for us. After a day of snotty-nosed sneezing, Calvin developed a cough and a fever of 102.6 degrees. Several hours later, I was amazed that the stubborn fever hadn't managed to break his twenty-seven-day seizure-free streak. However, despite alternate doses of acetaminophen and ibuprofen, at 1:30 in the morning a grand mal finally broke through, and a second one regrettably followed a few hours later. The kid is still sick.

Nevertheless, on Sunday, as on most days, I found things to be grateful for: Calvin didn't have a third seizure; he felt well enough to be interested in a car ride; though he didn't eat, he took in fluids; I still managed to get outside by myself to run a few miles. Practicing gratitude, however, doesn't mean I don't also lament Calvin's and our impossibly difficult and relentless situation.

Throughout the weekend, I thought about a social media post I'd seen in which its author expressed her belief in a heaven for the followers of Jesus. The specificity of her remark made me bristle a bit, understanding well that many if not most Christians are convinced that nonbelievers—no matter how virtuous—will be tormented in Hell for eternity; I've had friends and acquaintances tell me that's where I'm headed simply because I'm not Christian. Mostly, I laugh off what I regard as an absurd, fantastical, primitive invention. I went on to consider Calvin's innocent obliviousness to Jesus. I thought, too, about my many salt-of-the-earth Atheist, Jewish and Muslim friends who, though they know who Jesus was, do not claim him as their lord and savior. If there is a god, is "He" so conceited and merciless as to banish decent people to eternal damnation for their so-called indiscretion? Are we/they not God's beloved children, too? Shouldn't virtue be valued over appeasement?

I went on to recall an interview I did with a student of journalism who produced an audio profile of me during the height of the pandemic. She made a gorgeous, seven-minute piece about my life with Calvin. Her depiction is rich, though doesn't include my recorded musings on religion, Christianity, specifically. I surprised even myself when I told her that many aspects of Christianity offend me. I had never thought of it in those stark of terms before, but as I described sweet Calvin's miseries and struggles—his malformed brain, inability to adequately express his wants and needs, his helplessness and vulnerability, his seizures, the heinous transient and permanent side effects of epilepsy drugs and their withdrawal—my position crystallized. I lamented to her the "everything happens for a reason" and "God doesn't give you more than you can handle" platitudes that come my way all too often from well-meaning Christians when they learn about Calvin. To the former, I usually respond by saying I don't believe it for a second; to the latter, I counter by asking why, then, do people kill themselves?

Though raised Catholic, and despite the fact I'm fond of the presumed teachings of Jesus, I lost my religion ages ago, having first begun to doubt it with the tragic swimming pool accident of a best friend's two-year-old sister when I was fourteen. As the years have passed, I've become more awake to Christianity's patriarchy, sanctimony, power-lust, enrichment, racist and bigoted history, and the hypocrisy of some of its most ardent leaders and disciples, which doesn't negate the fact that, like all people, most Christians are good.

But, there is something else that troubles me: religion's depiction of the creator (assuming there is one) of our mind-blowingly vast and expanding universe as anthropomorphized, obstinate, immutable, callous, conceited, judgemental and unforgiving—a being, I'd argue, that seems made in man's image rather than the other way around. What exactly would be the motive for an allegedly omnipotent, merciful god to let "His" children suffer, to test them so harshly, setting up some of them—like Calvin and others who through no fault of their own are isolated and ignorant of Jesus—for certain failure? And if we puny humans are capable of forgiving each other's mistakes, shortcomings and most heinous offenses, why isn't God? What is the point of a fealty experiment, anyway? Shouldn't virtue be enough?

Knowing with the utmost conviction the answers to my own questions, I return to musing on gratitude—for the green canopy of trees, for a healthy body able to run free for miles by myself, for an adorable, affectionate child, a husband, friends and family who love me, for kind strangers and shearling slippers and smoked-chicken enchiladas and black-eyed susans and Nan's dahlias and lemon bars and Smellie dogs and cozy homes and blue ocean vistas and moody skies and screen porches and chilly mornings and warm breezes in the afternoon. Finally, I land again on imagining that wherever, whatever or whomever these gifts come from must unquestionably be free of judgement, an expansive and evolving universal beauty. And if perhaps it's a celestial energy or being, I imagine it to be no less than my pure son Calvin—a force of genuine and infinite acceptance and unconditional love.

8.29.2022

stronger?

|

| 2017 same old same old |

8.08.2022

running like the wind

While walking Smellie in the sweltering heat of Saturday evening, I passed the home of some friends who were in their backyard barbecuing. I heard the happy chatter of the couple with at least one of their children and perhaps one or two friends. The banter was uplifting and made me smile despite more than a tinge of sadness realizing in real time that Michael and I never have, never do, and never will have that experience with our son since he can't talk or engage with others in any kind of "normal" fashion. In fact—without exaggerating—I can probably count on ten fingers how many times Calvin has eaten a meal with us at the table. Unless friends come over, Michael and I always dine by ourselves as if empty nesters which, despite sitting constant vigil beside the baby monitor, might seem like a major bonus but in the bigger picture is a colossal loss.

Earlier in the day, I had run the Beach to Beacon 10K with about 7,000 other runners. I carpooled to the event with a neighbors' daughter, Clare, who is sweet as can be and is a serious runner. She picked up my bib and event swag for me the night before, and helped me navigate the event, which was my first-ever bona fide road race. Though it was 75 degrees with 85% humidity when the race began at 8:00 a.m., it was fun! Just before the race began I was able to hug my dear friend, Olympic Marathon Gold Medalist Joanie Benoit Samuelson, the event's founder, and she cautioned us to "please stay safe" in the heat. My goal was to finish without walking and to average a pace between 9:30 and 9:45 per mile. I came in a hair over that, which was satisfying considering the heat and the fact I had trained in earnest for just over two months. It feels good to finally be in the initial stages of getting back to my former athletic self, the one I pretty much abandoned when Calvin was born. Clare, by the way, placed fourth in the field of non-professional women with a pace of 5:59 per mile! Smokin'!

While among the stream of runners, as I smiled at the blaring, running-themed front-yard music, waved at the folks in fold-out chairs cheering and ringing cow bells, high-fived and fist-bumped the little tykes standing at the edges of yards cheering us on, I thought about what some of my friends had said to me before my race.

Just weeks prior to the race, when I was worried I hadn't trained enough distance, Joanie reassured me in a text:

"The crowds and runners will carry you in much the same way that you have carried Calvin."

The day before the race she added:

"Run like the wind!"

Her words gave me tears and chills, and I took them to heart. Other accomplished runner friends, my husband, and sibling athletes gave me advice about not overdoing it in my training, not going out too fast (I knew this from distance swimming), taking smaller strides on the hills (thanks Clare!), what to wear and what to eat and drink pre-race.

During the race, I concentrated on keeping my head up. I noted the glorious feel of the sun and wind and shade, the scenery, the tempo of my breathing. I focused on not scuffing my feet on the pavement lest I impede my own progress. And then, halfway in, I did think about Calvin and about carrying him all these years. I looked around at the close crowd of runners buoying me as if I were floating down a river out to sea. I thought about the pain of the endeavor and realized it was nothing compared to what my son endures when he seizes or suffers miserable drug side effects, or the agony he faced when he broke his hip at school. Having put it all in perspective, I was able to then forget about my little ball and chain for the rest of the race, because though I wanted to honor Calvin by doing something he might have been good at, I want running to be mine. I want at least one aspect of myself to be, for all intents and purposes, independent of Calvin since most of my life is Calvin-centric in a way altogether different from parents of neurotypical children—which is to say that my infant-toddler-teen will never grow up. I may forever be on guard, changing diapers and spoon-feeding, to say the least. And though I know parenting "ordinary" children comes with its own serious challenges, I will always lament never being able to experience the joys of things like shooting the shit with Calvin and his friends at backyard barbecues.

As I come partway off of the runner's high that I got during and after Saturday's race, and as I sit here at the top of the stairs mere feet from where Calvin is splashing in the bathtub, I realize that running—the time and space when and where I can drift and dream—is mine.

While editing this, I recalled a post I wrote over a year ago about a winning marathoner I passed often during my pandemic back-road drives with Calvin, and with whom I've since become casual friends. In the post, I wondered about his reasons for running, whether he had suffered losses, whether there was anything that grieved him, whether he might be running to escape a hardship. But as I type, I realize my ponderings were and are mere projections—a commentary on my own situation and hardships. I also realize that running for me isn't just about escaping all-things-Calvin. It's also an attempt to ground a self that is often sent emotionally reeling by the intense, frustrating and often sorrowful caring for my child and his chronic condition, and it's an effort to get reacquainted with my true, healthier, competitive and independent self.

And as I relive the Beach to Beacon 10K in my mind, the thing I remember most is not the pain, not the heat, not the hills, but the glorious feeling of running free like the wind.

|

| Me and Clare |

7.30.2022

to love life

We sat in the closeness of the sticky mid-morning heat, our bare arms and thighs touching. The rickety bench Woody gave me, one that dropped another screw recently, held us even as it swayed under our weight. I wrapped my hand around hers and kissed her cheek. We drank little rivers—she a sparkling citrus-scented water from a can, and I tap water held in a heavy green glass. We listened to a goldfinch sing as the wind swept through the trees. It felt as if we were the only ones in the world, and tears of sorrow came to us both as we contemplated life's tragedies.

During our walk earlier, she and I talked of mosquito bites, politics, running races, friendships, gardens, daughters, sons. Something flew up the open leg of her shorts and stung her repeatedly. I peeked into the back of her waistband and a bee—or was it a wasp?—flew out. She bent and plucked flat leaves of plantain, put them in her mouth, chewed them into a mash and applied tiny wads to the stings as a medicinal salve meant to draw the poison out.

"Everything we need is here for us," she said, meaning that nature is the original balm, then adding that we've just forgotten how to use it. I thought of Calvin's cannabis oil and how well it seems to help quell at least some of his seizures.

On our walk home, we stopped to cut—with permission—bunches of nodding sunflowers from our friends' backyard. Some of the smaller ones, which were still closed tightly like little fists as if reluctant to open to today's world, reminded me of my newly-born, four-pound, six-week preemie's apple-sized head and cinched brow. What a difficult yet extraordinary road it has been since then.

Later, when early evening came around and as I washed up dishes listening to my Calvin moan and rustle in his bed upstairs, I was again on the verge of weeping. My son is so often out of sorts or miserable, suffering from one thing or another inevitably brought on by seizures and/or their drug treatment. Though it had only been five days since his last grand mal, I could sense one coming by his bad balance, stubbornness, intensity, neediness, sour breath, eye poking, fingers in his mouth and mine, the new moon on the rise. I thought again about my earlier conversation with my friend. While strolling along a wooded path we had discussed abortion and the recent Supreme Court's abysmal decision to reverse Roe. I told her that, had I known for certain early on in my pregnancy that Calvin would be born missing most of the white matter in his brain which would cause him to be legally blind, uncoordinated, nonverbal, incontinent, cognitively impaired and—worst of all—be pummeled by thousands of uncontrollable seizures, I might have chosen to end the pregnancy to spare his suffering. To say that life for him is limited and presents major daily challenges, pain and miseries would be a gross understatement. Lamentably, there is so very little that Calvin seems to enjoy, mostly because he's been ruined by the drugs which cause him, at the very least, to be impossibly restless, making it harder, too, for me to live the life I want to live.

Just before my husband arrived home for the evening, I sat near the open French doors which look out onto the garden. There, while I reflected on my day and wrote this post, I came across this poem by Ellen Bass:

The Thing Is

7.23.2022

little enigma

I know it's been awhile since I've written. Calvin has had a bit of a hard time lately due to who knows exactly what since he can't tell us—it is always a mystery—but probably some combination of an increase in his newest epilepsy drug, Xcopri, and a recent decrease in his older epilepsy drug, Keppra. My guess is he is experiencing some withdrawal seizures and symptoms, and my bet is that the Xcopri and my homemade THCA cannabis oil is helping to quell some of them.

Suffice to say, I haven't had the wherewithal or the headspace to write. Instead, I've been training for a 10K running race called Beach to Beacon, which happens two weeks from today (I've never done a road race) and I've been taking loads of photographs of trees and flowers and water and my little enigma this past year, which I'll leave here for you to consider. Click on any of them to enlarge.

I hope, dear Reader, that your summer is going well as can be and that you're getting out and about. As for me, I'm enjoying my car rides with Calvin, and my runs and walks on the back roads and trails with or without Smellie, plus a bit of gardening, small and infrequent gatherings with friends, good movies, eating Michael's delicious meals in the screen porch, and this sanctuary of ours. And of course, I continue to live vicariously through others, perhaps even through you.

7.06.2022

like no other

|

| Simpson's Point |

6.28.2022

intimate decisions (american dystopia)

I've been pregnant twice. My sweet, pure, legally blind, nonverbal, incontinent, autistic, cognitively impaired, seizure-plagued son, Calvin, is my only child. At least three of my friends who were in committed relationships when their contraception failed were able to get safe, legal abortions after discussing the intimate decision with their partners. One of them was the mother of two, another went on to have two children, and the third remains child free. I'm not pro-abortion and I've never had one, but after suffering the miscarriage, I underwent a D and C. My only worry was that, because of my age, I might not get pregnant again. That worry was shortly replaced by a wholly different kind of worry: Calvin, my little apogee and abyss.

The recent Supreme Court reversal of Roe vs. Wade, which has eliminated Americans' constitutional right to abortion—aka body autonomy and reproductive freedom—is as astonishing as it disturbing. It serves as evidence of the Conservative majority's callousness, ignorance, and chauvinism.

Callousness—for the blatant disregard of the physical and emotional harm millions of girls, women and their families will suffer when they are forced to carry unplanned, unwanted or medically problematic pregnancies to term. Women and girls will die without access to safe abortion. They'll die in childbirth itself. When they have dangerous complications from miscarriages and stillbirths, they'll die foregoing access to medical care for fear they'll be suspected of attempting to abort in states that have banned the practice. Black girls and women, whose rates of maternal death are three to four times higher than whites, will disproportionately face the most dangers, as will poor people and other people of color. How are these circumstances not examples of depriving women and girls of their constitutional right to pursue life, liberty and happiness? Despite these lethal risks, anti-abortion advocates claim this decision is somehow pro-life. Moreover, anti-abortion advocates tend to oppose measures known to greatly reduce abortions such as easy access to contraception and comprehensive sex education, and social programs such as universal healthcare, paid family leave, childcare, universal pre-k and other programs aimed to help mothers and fathers avoid the financial and logistical hardship of raising children. It sickens and pains me to see and hear them celebrating this decision, this most recent version of American dystopia.

Willful ignorance—for the apparent refusal to seriously consider and truly understand—or care about—the infinite and deeply intimate reasons why millions of women and girls might want or need to have abortions: complications such as ectopic pregnancies, fetal abnormalities, extreme youth or advanced age, family size, financial woes, career aspirations, rape, abusive relationships, health of the fetus or the mother, or simply that they don't want children. Forcing women and girls to unwillingly carry their pregnancies to term is tantamount to torture. But these facts don't matter to a sanctimonious, sexist court which has relied on precedent from a century-and-a-half ago when women were not equal participants in society or government and were barred from voting; Alito cited in his draft decision an English jurist who defended marital rape and had women executed for “witchcraft.”

Chauvinism—for holding the erroneous, absurd and sexist notion that half of all Americans don't have a fundamental right to control their own bodies and destinies. As some wise woman said, if men could get pregnant, abortion would be a sacrament. Chauvinism—for the way the decision hastens our nation to a place of (worse) female subjugation and punishment. Chauvinism—for the way the decision thrusts us into an American dystopia where surgical abortions will again be clandestine, will again result in rape, and will again be dangerous and lethal. Again, women and girls forced to carry pregnancies to term will be unjustly denied their constitutional right to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness.

The Conservative Justices have scapegoated and punished girls and women by imposing their fundamentalist, patriarchal, religious and sexist agendas on them, ones to which a growing number of Americans—including some religious people—do not prescribe. The Justices used the absurd originalist argument that, because there is no explicit mention of abortion in the Constitution, women are not guaranteed access to it in their pursuit of liberty. It's worth noting that there is no explicit mention in the Constitution giving men the right to impregnate girls and women.

You know you're living in an American dystopia: when the rights of an eleven-year-old rape victim matter less than the zygote, embryo or fetus inside her resulting from that rape; when a government entity—particularly one made up mostly of conservative religious white men—attempts to control women's and girl's bodies by forcing them to carry pregnancies to term risking dire physical and emotional health outcomes, particularly in a nation that has one of the worst maternal mortality rates in the developed world; when imaginary lines drawn on a map of a nation where white colonialists slaughtered indigenous people and stole their land is what determines whether girls and women become the mothers to their rapists' children. Note: beware the anti-abortion push for a federal ban on abortion; if republicans gain control of congress this November, we'll be one step closer to that dystopia.

Our sweet boy Calvin, who I chose to have despite knowing he was missing most of the white matter in his brain, has made life for us very difficult and harrowing at times. I can't say for certain what I'd have done had we known earlier and for certain that things would turn out this way and that Calvin would suffer so. What I do know is that I wouldn't think of making that kind of deeply intimate decision for someone else. When our bodies are not our own to control, when legislators regulate them like commodities, we live in tyranny—an American dystopia—where, one by one, our other rights are at risk of being whittled away by a small group of powerful, callous, willfully ignorant and chauvinistic people who will never choose to hear our stories or walk even a few steps in our shoes.

|

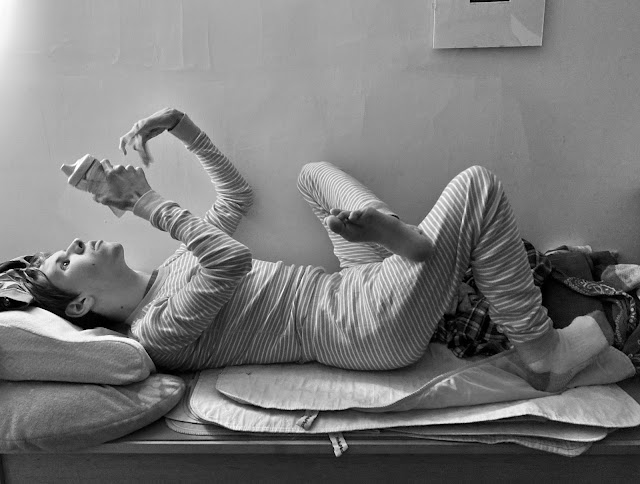

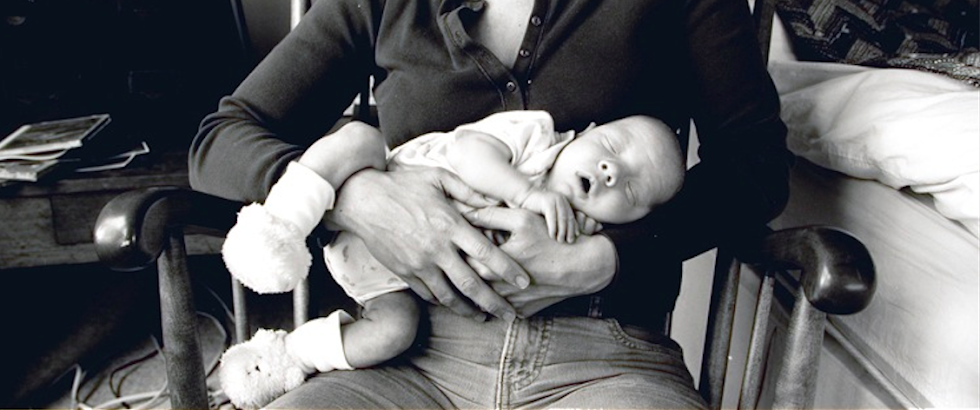

| Back when I was pregnant with Calvin, yet still child-free. Photo by Michael Kolster |