calvin's story

9.28.2020

necessary cleansing

9.26.2020

worried sick

Yesterday morning at 4:30, after I'd been tossing and turning for over an hour, the dreaded seizure came. It had been just six days since the last one. In the early evening the night before I had seen its approach, Calvin's telltale agitation, his finger-knitting and eye-poking common harbingers. Sadly, there isn't much we can do but lie awake worried sick waiting for it to happen while fretting over all things big and small—the supreme court, neglected inboxes, this filthy house, the election, social justice.

Since Calvin was two, he has had thousands of seizures. During them, he has bitten his cheek till it bleeds. He has struggled to breathe and turned blue. He has fallen out of bed and gotten bruised. He has succumbed to all kinds of dizzying side effects from antiepileptic medications—headaches, nausea, dyskinesia, ataxia, agitation, confusion, panic, anorexia, malaise, withdrawal. At least four times this year Calvin has taken a fall, usually on days before a seizure as he cranes his neck to stare at the sun. Sometimes he topples straight backwards as if he were timber. At others, he tips and drops to the side like a stone. Despite the fact that we've got our hands on him, he somehow manages to slip out of our grasp. The few times that he has hit his head, he was thankfully on the lawn, which is somewhat forgiving.

As I lay awake next to Calvin as he drifted back to sleep after the seizure, I thought about our litany of miseries—his hospitalizations, his injuries, his seizures, his close calls, the difficulties in caring for him. The only thing we don't have to worry about are his medical costs thanks to decent health insurance through Michael's job, plus supplementary state Medicaid just for Calvin.

The healthcare costs for a child like Calvin are astonishing and include bills for medications, examinations by his primary care provider, neurologist, endocrinologist, urologist, gastroenterologist, neuro-ophthalmologist, pulmonologist, orthopedic surgeon, and x-rays, sonograms, CT scans, MRIs, EEGs, sleep studies, splints, orthotics, glasses, eye surgeries, nuclear medicine tests, ambulance rides, emergency department visits, hospital admissions, intubations, IVs, blood work, insurance premiums, copays, deductibles, and in-home nursing when there's not a pandemic.

Back in 2008 near the start of the Great Recession, my husband's case for tenure at Bowdoin College was in doubt. We spent weeks worrying about what we'd do if he were released into the worst job market since the Depression in a field with scant opportunity. If Michael were ultimately denied tenure and unable to find a new job, we worried that healthcare insurance premiums and deductibles would be cost prohibitive, assuming we could even get insurance for Calvin considering his myriad preexisting conditions.

In the end, despite the uncertainties, Michael was awarded tenure. This meant we were not faced with the dire situation in which many Americans find themselves today having lost their jobs and, thus, their health insurance due to a recklessly managed and consequently rampant pandemic.

Over the years, I've read and heard stories from countless Americans who have gone bankrupt due to massive healthcare costs from everything from appendicitis to cancer. From its inception, the Affordable Care Act (ACA), aka Obamacare, which provides healthcare to over 20 million Americans and requires insurers to cover preexisting conditions, has been attacked by republicans. Prior to the ACA, insurance companies regularly denied health coverage to people like Calvin, or charged exorbitant premiums to do so. The Biden/Harris ticket aims to expand the ACA to include a Medicare option for anyone who wants it. In stark comparison, the current administration is actively fighting to destroy the ACA despite still not having a plan to replace it; the Supreme Court will hear oral arguments on the fate of the ACA one week after the November election.

Americans' healthcare—a necessity to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness and essential for a safe, secure, healthy, and prosperous nation—hangs in the balance, leaving many of the most vulnerable Americans to lie awake at night worried sick and getting sicker. In the most prosperous nation in the world in which so many people like to claim that all lives matter, none of us should have to live that way.

|

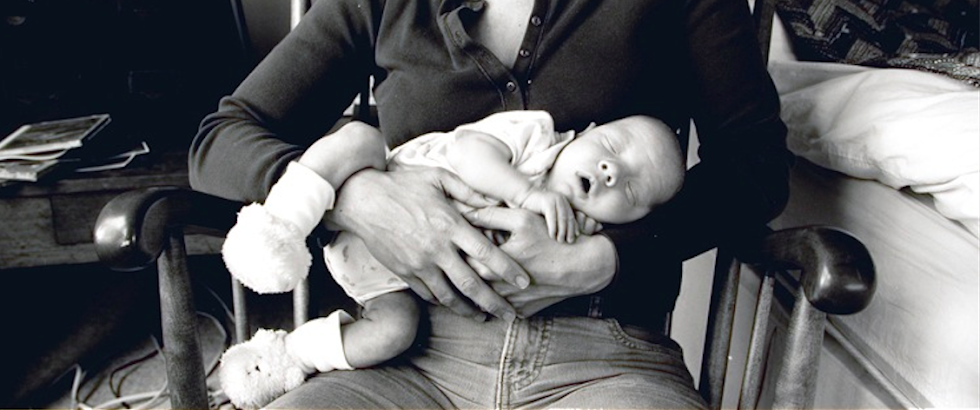

| Calvin in the hospital after a prolonged seizure, March 2006 |

9.21.2020

gut punches (and others)

"Oh, no!" I cried out, upon learning of Supreme Court Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg's death, my verbal reaction reminiscent of Michael's response when he heard that a dear friend had taken his own life.

On the heels of my grief and disappointment over the news of RBG's passing came the regrettable recognition that the current administration would move quickly to replace her, no doubt with a nominee apt to, at the very least, kill the Affordable Care Act and its mandate covering preexisting conditions, broaden avenues for continued voter suppression, and subvert (further) the body autonomy of American women.

My mind went into a frenzy recalling myths about abortion and the ways in which conservative men, for the most part, have for decades worked hard to politicize and legislate (away) women's reproductive health and freedom by limiting access to birth control, and by further diminishing the reasonably small window in which most abortions are allowed to be performed. Republican-led, mostly-male legislatures continue their aim to tighten regulations and mount burdensome hurdles so as to strictly limit the number of the nation's abortion clinics making it difficult for women, especially those who are poor, to access safe and legal procedures. Consider, too, the disingenuous pro-life claims, borne out in attempts to stifle proven, best methods of preventing unplanned pregnancies and abortion, such as free and accessible contraception, family planning and comprehensive sex education. Despite the fact that neither the Old Testament nor the New mentions abortion—not one word—many people cite their religious beliefs as the basis to condemn it. Noteworthy, too, is that Christian women make up nearly two-thirds of those who choose to have an abortion.

I became further vexed pondering the fact that many who profess their belief in the sanctity of life also support capital punishment—state-sanctioned murder—while still others suggest allowing abortion in the case of rape or incest, thereby belying their pro-life claims. And what of the growing number of Americans like me who aren't religious, who don't buy into the notion that a zygote or fetus has more rights than its pregnant mother, who don't condone the legislative and punitive coercion of women to carry unintended pregnancies to term? Should the religious freedom of some Americans supersede the basic human rights of others? I don't think so. Moreover, consider the fate of malformed fetuses which will endure brief though agonizing lives if their mothers and fathers are not allowed the option of sparing them certain pain and suffering after birth.

All the while—incomprehensibly, if not for the current patriarchal paradigm—the subject of making accountable the male impregnators never seems to enter the political discourse or legislative debate regarding abortion. How convenient. This continued strangling of women's reproductive rights and personal empowerment and freedom is insufferable—a literal and figurative gut punch. And the stomach-churning truth is that now, with RBG's death, the specter of yet another diehard conservative on the Supreme Court makes women's hard-fought sovereignty as precarious as ever.

Obviously, I'm pro-choice, which is not the same as pro-abortion. However, were I aware early in my pregnancy the extent to which Calvin's brain anomaly would lead to his miseries, I wonder what I would have done. I think I know, but I can't be certain. Regardless, I don't believe I have the right to decide the outcome of other women's planned or unplanned pregnancies, which impact their mental and physical well-being, the stability of their families, the trajectory of their careers, and the health risks to themselves and/or their unborn.

At a time when over three-quarters of all Americans support a woman's right to choose, and when one in four American women access abortion, the passing of Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg leaves American women vulnerable to a handful of privileged, conservative, male, Supreme Court justices, all with Catholic roots. As deft as these conservative justices are on the Bench, I have my doubts that they are capable of fully considering, from a woman's unique perspective, the sweeping risks and considerations, the threat to very private, personal and constitutional freedoms and equal access to life, liberty and the pursuit of happiness that unintended, unhealthy or hopeless pregnancies—or a government mandate to take those pregnancies to term—may represent.

As I mused on the terrible dilemma of losing one of America's best champions of gender, religious and racial equality, I recalled The Notorious RBG's use of a statement by the abolitionist, Sarah Grimké:

I ask no favor for my sex; all I ask of our brethren is that they take their feet from off our necks.

This November, get out there and vote. Know how to vote in your state. Vote early. Vote by mail. Complete your ballot carefully and put it in your city's drop box. Be prepared for long lines if you vote in person. Vote as if your healthcare is in peril. Vote as if your or your partner's reproductive rights are at risk. Vote as if corporations have more rights than you do. Vote as if your right to vote is in jeopardy. It's all hanging in the balance.

Now is not the time to pull any punches.

9.16.2020

"i am" poems

In response to my pen pal's letter, I told him I had recently finished the book, Reading with Patrick. It's author, Michelle Kuo, writes deftly and movingly about her time as a high school teacher in a small Mississippi Delta town. I went on to tell my pen pal that the author asked her students to write "I am" poems. I wrote a quick one in my letter to him:

I am strong

I wonder how life would have been if my son were "normal"

I asked my pen pal if he might want to write an "I am" poem and send it back to me. I am hoping so.

At the end of my letter to him I drew a picture of our dog, Smellie, then signed off by saying, Know that I am thinking of you. I folded the pages around a self-addressed stamped envelope plus a family photo taken seven years ago which I discovered, slightly crumpled, in the back of my desk drawer.

I can't help but wonder what my son Calvin, who is nonverbal, cognitively and physically disabled, might write in his own "I am" poem if he were able. But since he isn't, I wrote a version for him, imagining him capable of certain complex thoughts:

I am a fighter

I wonder why I'm not going to school anymore

I hear my mom drop the F-bomb a lot

I see my mom get annoyed with me sometimes

I want to be able to do things by myself

I feel frustrated when I'm not understood

I cry when my head and tummy hurt

I understand that I am loved

I dream of being able to speak

I try to do my best at everything

I hope one day my seizures stop

Rereading my poems, I'm reminded of how vital it is to see life from another person's perspective, which is the main reason I was interested in raising a child. I want to understand why and how other people grieve. I want to bear witness to other's struggles and to feel empathy. It seems that the America we live in—one which too often embraces the myth of rugged individualism and mantras like, Don't tread on me—suffers from a lack of understanding and empathy for those who face certain stresses and obstacles in their daily lives which hinder their ability to live life fully, enjoy liberty and pursue happiness. I'm thinking of Americans who are homeless, hungry, hurting, cold. I'm thinking of Americans who are disabled, hated, disenfranchised, imprisoned. I'm thinking of Americans who don't have jobs, health insurance, savings, and those who can't vote.

I slide my folded letter and family photo into an envelope, address it, seal it, stamp it and pop it into the mailbox for its trip to Alabama. Doing so, I imagine my pen pal passing long hours in his cell. I consider the fact that he never got the chance to vote and will likely never be able to vote for the leaders who will write laws and policy which directly affect him. I think of the number of innocent people who are imprisoned and on death row who are disproportionately people of color. I wonder what kinds of "I am" poems they'd be writing if they could.

|

| Photo by Michael Kolster |

9.13.2020

where i roam (and don't)

When six o'clock arrives and we put Calvin to bed, I can relax a little bit, have a glass of wine. Once a week, or so, we visit with another couple for a limited time at a safe distance outside; I get energized. At night, Michael and I hunker down with a good movie or to read, then hope to get a decent sleep. Too often, we're rattled by the sound of Calvin's seizure scream; he has them once or twice a week. Like the pandemic, they're unsettling. I dread them. I lose much-needed sleep.

Like last night, lying next to Calvin in the seizure's wake, in my mind I try to roam to faraway places. I go to where the haze in the air is mist. I visit familiar cities which are gleaming. I go to where vistas are myriad, waters are calm and azure, fields are vast and green. I go to where there's no pandemic and where Calvin doesn't seize. I dream of times when leaders are virtuous, and the future isn't bleak.

9.08.2020

present trouble

Last week, I heard and read about the murder of yet another unarmed Black man at the hands of police, this time in Rochester, New York earlier this year. His name was Daniel Prude. He had left his brother's house in an erratic, psychotic, state. His brother called the police for help. Instead, Daniel became another victim in this nation's historic and present trouble of violence against Black people.

It was nighttime in March. By the time the cops arrived, Mr. Prude had taken off his shirt and long johns and was running around naked in the cold. The officers handcuffed him and put a spit mask over his head. Even as Daniel pled with officers to remove the mask, they held him down, his face pressed into the pavement, until he passed out and his pulse stopped. Though he was revived in the ambulance, he never regained consciousness. He died seven days later.

We know of dozens upon dozens of stories like this—unarmed Black men, women and children being murdered by police and vigilantes. Each account is sickeningly reminiscent of past ones—Jacob Blake, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Eric Garner, Tamir Rice, Philando Castile, Trayvon Martin. Unless we as a nation do something different—unless we reform the police and evolve as a society—these atrocities will continue.

Despite gains made during the Civil Rights Movement, Black people in America are still treated by many in law enforcement and others as subhuman. As if animals, they are falsely feared and made into monsters. They are regularly maligned as criminals. The Black Lives Matter movement is vilified as sinister, though their platform is righteous and inclusive, its simple goals dignity, opportunity and equality for Americans who, since slavery, continue to be exploited, terrorized, lynched, targeted, marginalized and abused. Some people's refusal to say, Black lives matter, serves as ample evidence of the need to underscore that very truth.

I worry about the well-documented infiltration of racism, White supremacy and far-right militancy into our nation's law enforcement, and its subsequent effect on communities. I understand what a privilege it is to have white skin and to jog, drive, jaywalk, shop, hike, play, loiter and prank with impunity. I know what it is to be the mother of a child who is misunderstood and undervalued by many. I read too many accounts of boys with autism and other mental health problems being killed by ill-trained police. I hear other's messages which are conveyed to me in real words and expressions of contempt and indifference:

Look at that kid. What's wrong with him? Shut that child up. Why can't she control him? He doesn't belong here. He's disgusting. I don't want to have to look at him. Pretend he doesn't exist.

I see a similar contempt for and misunderstanding of Black people and their movement. I hear people scapegoat and victim-blame African Americans, hear people regularly assign criminality to Blackness. I hear their message in words and expressions of contempt and suspicion of Black victims:

He must be guilty of something. If only he had complied. He had it coming. He was a monster. The officer feared for his life. He had drugs in his system. It looked like he had a weapon. Why did he run? He shouldn't have been there doing that in the first place.

Yesterday morning I heard an excerpt from a James Baldwin essay entitled, The White Problem. Though written in 1964, it still resonates today:

The people who settled the country had a fatal flaw. They could recognize a man when they saw one. They knew he wasn’t anything else but a man, but since they were Christian and since they had already decided that they came here to establish a free country, the only way to justify the role this chattel was playing in one’s life was to say that he was not a man. [Because] if he wasn’t, then no crime had been committed. That lie is the basis of our present trouble.

I consider, again, the state-sanctioned murder of innocents and "undesirables" in Nazi Germany and in this nation. I lament the dog-whistle politics of the current administration. I say a secular prayer for the men and women who are fighting for equal justice in a nation that still hasn't atoned for its sins or lived up to its original promises. I think about my new pen pal who is on death row, whose first letter to me was humorous, heart-rending and tragic. He doesn't deserve to be there; no one does.

As always, I muse on my son Calvin who, though nonverbal, autistic, physically and intellectually stunted and disabled, is as worthy and lovable as any of us. Then, I imagine those like Daniel Prude, whose lives were snuffed out in the street as if they didn't matter. No doubt they were worthy and madly lovable too.

9.01.2020

the bright side

After stopping Epidiolex several weeks ago, Calvin had "only" six grand mals in August instead of the ten he had in the span between late July and early August. Notably, his behavior is much improved overall. He's had far fewer manic episodes and is sleeping more soundly. Two-and-a-half years since his last dose of the benzodiazepine, Onfi, he is doing well in the wake of seizures; no longer does he experience what seemed like panic attacks which included a pounding, racing heart, clammy hands, hyperventilating, fidgeting and patting the bed for hours in the middle of the night.

The weather is gorgeous. Sunny. Breezy. Mild. Dry. Humidity having vanished, skies are as blue as they are on any given day in the West.

Calvin is doing well sitting on the potty. Not perfect, but I'll take any bit of progress he can give me, including far fewer dirty diapers. He's getting used to the routine of washing his hands, though I still have to help him quite a bit. He seems like he is understanding us better when we say things like, "don't bite that" or "let's go for a car ride."

Only rarely is he grinding his teeth or poking his eye. He still loves hugs and car rides. He doesn't wake me up as much at night.

Joe picked Kamala. She said yes. The democratic platform is righteous.

The first-year college students are in town, wearing their masks outside, walking six feet apart. When we stroll past each other, I smile and tell them how nice it is to have them here. They say thank you and tell me how good it is to be on campus. So far, only one of them has tested positive for coronavirus; He has to quarantine for two weeks, which makes me sad.

I just got my first letter from the man on death row who has become my pen pal. I hope I can make a difference in his life. He has already made a difference in mine.