As I begin to write this, Michael Brown’s parents are burying their son somewhere in Missouri. The thought of them standing before his grave, tears in their eyes, joined by a community of mourners gives me great pause, and I become mindful of sorrow's gravity tugging at the corners of my eyes and mouth, of the knitting of my brow. And when I Google images of his mother, and of others grieving, I see myself in their eyes.

In a stream of consciousness, I think of Ronan whose life was cut short by Tay-Sach’s disease before the age of three. I think of my high school friends, one who succumbed to leukemia and another who died from a cerebral embolism. I think of my friends’ children Kelly and Tyler and Will and August and Kevin who all died from complications of chronic conditions, some related to epilepsy. Though tragic, I don’t see their deaths as unfair or fair. Nature is indiscriminate.

Then, the image of Michael Brown’s crumpled, lifeless body flits across my screen, a river of blood gushing from his head over hot pavement, and I am reminded of Travon Martin, Oscar Grant, Renisha Marie McBride and Eric Garner, all unarmed black victims that died—unfairly—in what I see as an epidemic of race-based hatred.

I cannot think of these sorry deaths without considering the cruel and racist things that I’ve seen and read on social media, that I’ve heard over the years coming from the mouths of white people, even at times from my relatives. So many, it seems, are in denial, content to be blind to the subtleties of their own bigotry and in doing so perpetuate the racial divide. It seem so few recognize their complicity and so the blame falls back on the victims—the scapegoats—while the perpetrators whine, complain, denounce, vilify, and justify their wrongful actions with vitriol. I imagine that few choose to step into the victim's shoes, to try to see the world from their perspective, simply because the victims are black.

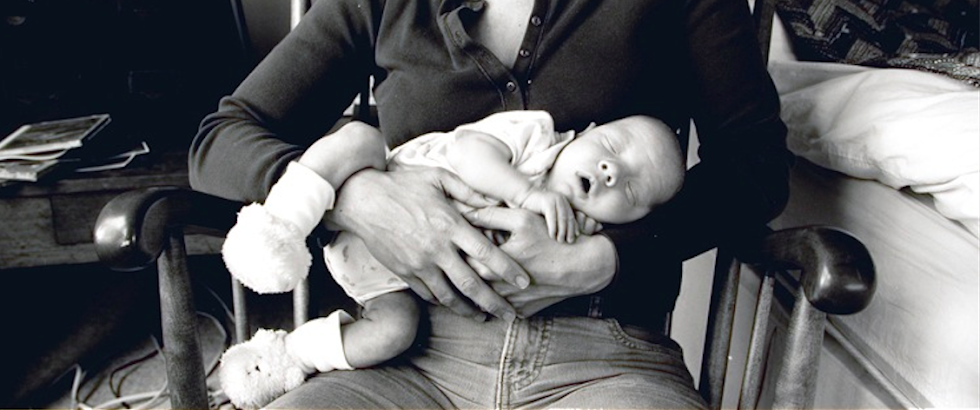

To me, the injustices are clear, perhaps because of my five-year relationship with an African American man, perhaps because I have long since been drawn to those different from me, perhaps partially due to the marginalization we have experienced because of our disabled son, Calvin, beside whom I feel the burning stare of mothers who, in their eternal gawks, seem to lack any desire for understanding or capacity for empathy. Perhaps my distant travels, or visiting homes of the poor, or living amongst the different faces and races and classes who were my neighbors in 1990s San Francisco has opened my eyes to others' struggles. Or, perhaps simply being a woman who has faced discrimination, scary catcalls and rude remarks, nasty looks, offensive slights, who has been assaulted, maligned, underestimated, misjudged and neglected by white men, gives me the tiniest hair of insight—an atom of a glimpse—into what it might be like to be black in this country.

Over the years I’ve heard scores of stories from white people who insist that their pet dogs are racist. They are always the same: big black "dude" (never "man") comes to door. Dog goes ballistic. Our dog Rudy used to bark at men wearing sunglasses and hats, but he was no racist. When I’ve had to endure these tedious stories, to which there is often much laughter from the teller and their cronies but not from me, I always think to myself that the dog’s reaction—dogs being completely intuitive creatures—is simply an extension of its owner’s muted, prejudiced response. Because to be racist is to believe that one particular race is superior to another, which we all know a dog is incapable of doing.

Sorrow and writing this post make my eyes tired. I think of the hateful, sickening comments by white supremacists masquerading as respectable citizens, and the flabby platitudes I've been hearing, like, "Why can't we all just get along?" I know the answer lies in openness, in loving, in learning about our histories, our struggles—shared and otherwise—in understanding each other's plight, in being accountable for our own actions and words, in being inclusive and recognizing when someone, even an entire race, has been—and continues to be—wronged, and deciding to do what is in our power to right it, whatever that might be. The way I see it, we can only do that if we decide to step into someone else's shoes, and to finally try to see ourselves in their eyes.

In a stream of consciousness, I think of Ronan whose life was cut short by Tay-Sach’s disease before the age of three. I think of my high school friends, one who succumbed to leukemia and another who died from a cerebral embolism. I think of my friends’ children Kelly and Tyler and Will and August and Kevin who all died from complications of chronic conditions, some related to epilepsy. Though tragic, I don’t see their deaths as unfair or fair. Nature is indiscriminate.

Then, the image of Michael Brown’s crumpled, lifeless body flits across my screen, a river of blood gushing from his head over hot pavement, and I am reminded of Travon Martin, Oscar Grant, Renisha Marie McBride and Eric Garner, all unarmed black victims that died—unfairly—in what I see as an epidemic of race-based hatred.

I cannot think of these sorry deaths without considering the cruel and racist things that I’ve seen and read on social media, that I’ve heard over the years coming from the mouths of white people, even at times from my relatives. So many, it seems, are in denial, content to be blind to the subtleties of their own bigotry and in doing so perpetuate the racial divide. It seem so few recognize their complicity and so the blame falls back on the victims—the scapegoats—while the perpetrators whine, complain, denounce, vilify, and justify their wrongful actions with vitriol. I imagine that few choose to step into the victim's shoes, to try to see the world from their perspective, simply because the victims are black.

To me, the injustices are clear, perhaps because of my five-year relationship with an African American man, perhaps because I have long since been drawn to those different from me, perhaps partially due to the marginalization we have experienced because of our disabled son, Calvin, beside whom I feel the burning stare of mothers who, in their eternal gawks, seem to lack any desire for understanding or capacity for empathy. Perhaps my distant travels, or visiting homes of the poor, or living amongst the different faces and races and classes who were my neighbors in 1990s San Francisco has opened my eyes to others' struggles. Or, perhaps simply being a woman who has faced discrimination, scary catcalls and rude remarks, nasty looks, offensive slights, who has been assaulted, maligned, underestimated, misjudged and neglected by white men, gives me the tiniest hair of insight—an atom of a glimpse—into what it might be like to be black in this country.

Over the years I’ve heard scores of stories from white people who insist that their pet dogs are racist. They are always the same: big black "dude" (never "man") comes to door. Dog goes ballistic. Our dog Rudy used to bark at men wearing sunglasses and hats, but he was no racist. When I’ve had to endure these tedious stories, to which there is often much laughter from the teller and their cronies but not from me, I always think to myself that the dog’s reaction—dogs being completely intuitive creatures—is simply an extension of its owner’s muted, prejudiced response. Because to be racist is to believe that one particular race is superior to another, which we all know a dog is incapable of doing.

Sorrow and writing this post make my eyes tired. I think of the hateful, sickening comments by white supremacists masquerading as respectable citizens, and the flabby platitudes I've been hearing, like, "Why can't we all just get along?" I know the answer lies in openness, in loving, in learning about our histories, our struggles—shared and otherwise—in understanding each other's plight, in being accountable for our own actions and words, in being inclusive and recognizing when someone, even an entire race, has been—and continues to be—wronged, and deciding to do what is in our power to right it, whatever that might be. The way I see it, we can only do that if we decide to step into someone else's shoes, and to finally try to see ourselves in their eyes.

You are a good person, Christy....the kind that restores my faith in humanity. You are absolutely right in your comments and reactions, and if we had lots more people like you, our world would be a better (i.e., happier, more productive, more nurturing, etc.) place. Thank you for writing this.

ReplyDeleteI wish more people were like you. That's all.

ReplyDeleteYou are singular in your ability to capture these current events, these tragedies, particularly, and weave them into personal meditation. So powerful

ReplyDelete